Coastal Taipan: An Introduction

Text by Brian Barnett (Originally published in Thylacinus in 1986. Reprinted in Monitor Vol.10 Issue 2/3 1999)

The Coastal Taipan is one of Australia’s largest venomous and most dangerous snakes, occurring widely in northern Australia with an endemic sub-species in New Guinea (Cogger, 1983). In recent years its popularity in reptile collections has increased. Here in Victoria, we are more fortunate than some of our interstate counterparts in that private keepers are allowed to legally keep these reptiles.

Captives are alert and by snake standards appear to be highly intelligent. This paper has been written in response to repeated questions by colleagues in relation to my previous successes in breeding the species.

Coastal Taipan: Materials and Methods

Eight females and two males contributed to the breeding results of this paper, and throughout the tables are numbered for cross reference. An additional female (No. 9) was used to obtain the results in the section relating to growth rates.

Eight females and two males contributed to the breeding results of this paper, and throughout the tables are numbered for cross reference. An additional female (No. 9) was used to obtain the results in the section relating to growth rates.

Female 1. Collected from the wild as a gravid specimen, Rockhampton, Queensland, 1972.

Female 2. Collected from the Cairns region, north Queensland, 1977.

Female 3. Collected from the Cairns region, north Queensland, 1977.

Female 4. Born Feb. 1978 from female 2 & male 2.

Female 5. Born Feb. 1978 from female 2 & male 2.

Female 6. Born Oct. 1980 from female 3 & male 2.

Female 7. Born Oct. 1980 from female 3 & male 2.

Female 8. Born Dec. 1981 from female 5 & male 1.

Female 9. Born Dec. 1981 from female 5 & male 1.

Male 1. Born Feb. 1978 from female 2 & male 2.

Male 2. Collected from the Cairns region, north Queensland, 1977.

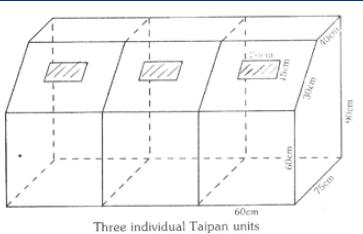

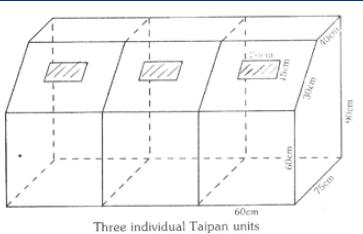

The adult snakes are housed individually in cages designed to maximize the use of the space available in a confined area. The design allows other cages to be placed on top and also offers a degree of safety without the normal top or front opening door or lid. The hinged lid is set at an angle of 45 deg. reducing the area of the front and top but resulting in a module with easy and safe access. See Figure 1 in Barnett (1978).

The floor area of each individual unit measures 60cm x 75cm, the height at the back is 90cm and the front height is 60cm. A viewing window, 20cm x 15cm, is fitted into the particle board lid.

Each new born clutch is housed in a series of three top opening cages each measuring 60cm x 48cm floor area x 46cm in height. A viewing window, 36cm x 18cm, is fitted into the lid.

Each new born clutch is housed in a series of three top opening cages each measuring 60cm x 48cm floor area x 46cm in height. A viewing window, 36cm x 18cm, is fitted into the lid.

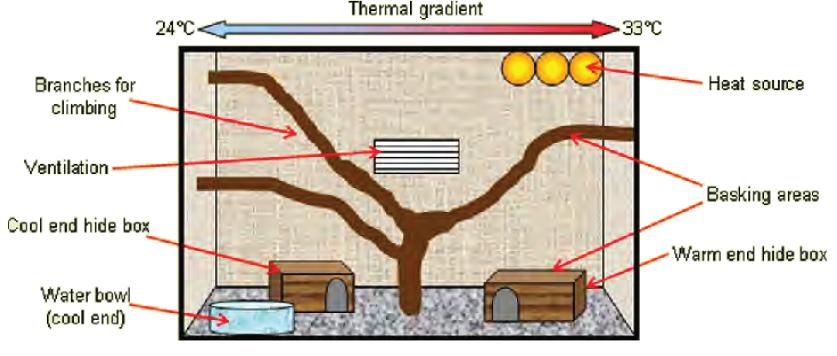

Pre-washed fine aquarium gravel is used as the ground cover and regularly topped up as the soiled areas are scooped out. A rock of suitable size is also placed on the floor area to be of assistance in sloughing and to block the hide box entrance whilst cleaning.

A wooden hide box, floor area 45cm x 20cm and 15cm in height, is supplied in each adult unit. These have hinged lids. The newborns are supplied with upturned plastic cereal bowls with a small entrance opening cut out of the side. In particular with the young, the hide bowls are constantly used and the young seem far less nervous than those that were not given hide bowls in the past.

Similar plastic cereal bowls are used as the drinking water containers. They are of the stackable type which fit tightly into each other. One is fixed to the floor of eachunit and the other is placed within this one. It is easily removed and replaced as fresh water is supplied. The fixing of one bowl to the floor eliminates any possible upturning of the second bowl and subsequent spillage.

A plastic vent, 12cm x 7cm, is fitted into the lid or wall of each unit. No natural light is supplied and each unit receives daylight hours of lighting by means of incandescent bulbs (15 watt). However, the reptile house itself is fitted with 1.2m ‘True-Lites’ throughout and this provides additional lighting during daylight hours.

Heating to the adult units was initially supplied by 150 watt Infra-red globes. This was later changed to a series of three 40 watt blue coloured incandescent globes in each unit. The blue globes are used to keep the night time hours in relative darkness when these lights may be on. The heating lights are controlled by a thermostat and each unit maintains a temperature of 26 – 28 degrees Celsius. This temperature is maintained through the year and no seasonal changes are made.

Feeding of the adult snakes is year round and on average three times per month. Six mice or one rat to a weight of around 150gm is readily taken per feed. The newborns and sub adults are fed on a rotation system and depending on time and food available may be fed up to three times per week.

Results - Also See Images of Tables (At the end of this post)

The male is introduced to the female immediately following the sloughing of the female. In the adult snakes sloughing occurs six to seven times per year at intervals of 46-67 days, mean 58 days, giving adequate opportunities for introductions. Normally, copulation occurs within hours and continues for up to six hours. The male is removed following the completion of copulation.

The male is introduced to the female immediately following the sloughing of the female. In the adult snakes sloughing occurs six to seven times per year at intervals of 46-67 days, mean 58 days, giving adequate opportunities for introductions. Normally, copulation occurs within hours and continues for up to six hours. The male is removed following the completion of copulation.

The snakes have been successfully mated over seven months of the year from mid autumn, through winter and into mid spring. No matings have been achieved during the summer months (table 1(a) and (b).) although introductions were made. N. Charles records one mating in early December (Shine & Covacevich, 1983). The most productive period being late August – early September.

The age of the females at first introduction was varied but two individuals were first mated at 20 months of age when their total body length was approximately 2 metres. As the Taipan matures at a much smaller size than this, 78cm SVL for males and 101cm SVL for females (Shine & Covacevich, 1983) it should be possible to breed them at an even earlier age. I have achieved the maturity sizes documented by Shine & Covacevich (1983) with several specimens at five to seven months.

A second mating for the year was recorded for three individual specimens. The previous matings were all early in the mating range, months four, five and six, and the duration between matings was 134, 77 and 93 days. The second matings were all achieved in the more regulation period of late winter, early spring.

Coastal Taipan: Egg-Laying

The eggs are laid in the hide box 11-14 days following the pre-laying slough, a feature also observed at the Melbourne Zoo (Banks, 1983).

No nesting material is provided and the female coils tightly, creates a shallow depression in the gravel and commences laying. I have been present for most of the layings and the majority of eggs have been removed individually, with a spoon scoop, with the female showing little concern in this intrusion.

The laying of five individual clutches were recorded for periods between egg laying. Depending on the size of the clutch and the number of smaller infertile eggs, which were deposited at a faster rate, the laying period ranged from six hours 16 minutes to seven hours 58 minutes. The mean period between individual eggs of the five clutches was 29.4 minutes (23-37).

The laying of five individual clutches were recorded for periods between egg laying. Depending on the size of the clutch and the number of smaller infertile eggs, which were deposited at a faster rate, the laying period ranged from six hours 16 minutes to seven hours 58 minutes. The mean period between individual eggs of the five clutches was 29.4 minutes (23-37).

Two clutches, from the one mating, were recorded from two individual specimens (Table 2), indicating sperm retention, a phenomenon also recorded by other herpetologists (Peters, 1972; Banks, 1983). The inter-clutch periods were 66 and 69 days. The fertility rates were 44 & 75%. The period from copulation to oviposition in all but one instance ranged from 61-85 days, mean 69 days (Table 2).

Clutch No. 19 was laid 155 days following the only observed mating. Although a male was present in her cage for several days up to 82 days prior to her laying, no indication of attempted mating was observed and under the conditions that they are kept, the period over which copulation occurs and my regularity of checking such introductions, I believe that this laying would be the result of sperm retention from the earlier observed mating. The female had not been bred previously and had shown no signs of being gravid in the expected period from the observed mating. It did not come up for its pre-laying slough anywhere near the time that it would have been expected in the range after the observed mating. It also laid well outside the range of all other clutches (February) and in normal circumstances this would be the result of a summer mating, the period in which I have not recorded any matings or the males having shown any interest in the females.

The following data on eggs of Oxyuranus scutellatus has been determined from Table 3.

- Mean clutch size: 14 eggs (9-20).

- The fertility rate was 78% (40-100).

- Mean (fertile) egg length per clutch at oviposition: 56.4mm (47.6 – 65.8), n = 16.

- Mean (fertile) egg diameter per clutch at oviposition: 32.4mm (29.4 – 34.8), n = 16.

- Mean (fertile) egg weight per clutch at oviposition 32.9gm (24.2 – 36.7), n = 13.

Coastal Taipan: Incubation

The eggs are incubated in clear top plastic bread containers using vermiculite as the medium (Barnett, 1981. 100ml of water is added to 150g vermiculite giving the medium a depth of 3cm in the container. A fine spray of water is added at a future date if required. The relative humidity is kept high. The temperature range during incubation is 29.5 – 32 degrees Celsius.

Coastal Taipan: Hatching

Pre-hatch measurements and weights (1-2 days before slitting) were taken of six clutches and although minimal, all but one clutch registered weight loss. The clutch with the weight gain averaged 0.4g/egg. Weight losses per clutch varied from 1.4-5.0g/egg. Lengths varied from a gain of 0.5mm to a loss of 0.6mm/egg. The diameter varied from a gain of 0.7mm to a loss of 0.5mm/egg.

Pre-hatch measurements and weights (1-2 days before slitting) were taken of six clutches and although minimal, all but one clutch registered weight loss. The clutch with the weight gain averaged 0.4g/egg. Weight losses per clutch varied from 1.4-5.0g/egg. Lengths varied from a gain of 0.5mm to a loss of 0.6mm/egg. The diameter varied from a gain of 0.7mm to a loss of 0.5mm/egg.

Five completed clutches were not incubated. Several were not required whilst others were used to photograph and collect embryos at varying stages and experimenting with the open egg in a humicrib (Barnett, 1980).

The incubation periods ranged from 62-71 days (n=15), mean 67. The percentage of eggs hatching from those placed under incubation ranged from 67-100% - mean 94% (n=15).

Upon slitting the eggs the young snakes usually emerge within 1-2 days. The young were weighed and measured at birth and all clutches are summarized in Table 4. Clutch #8 was the exception in size and weight and several of the very low weight range in the other clutches were found to have encountered restrictions on food supply with in the egg. The tail measurements of the young averaged out to 15% of the total body lengths.

Coastal Taipan: Rearing of Young

Each clutch of young is housed in a series of three cages as described in ‘Materials and Methods’. The middle cage is only used for feeding and the snakes are offered food individually. As one snake is moved from one cage, is fed in the middle cage and is then moved onto the other end cage. This is repeated until all the young have been fed and the next feed is a transfer back to the other end. Stubborn feeders can be left in the feed section overnight. I have found this rotation system to be very effective with raising young and can save valuable time whilst maintaining a large collection.

The young Taipans prefer moving prey and many have been reluctant to accept day old mice whilst readily accepting pre-weaner mice. The average sized hatchling Taipan is quite capable of eating a mouse up to 10gm in weight. Unlike the snap and release action of the adult snakes, the young attain a firm grip on the mice. This action may continue for a month or so when it changes to the snap and release method.

The young Taipans prefer moving prey and many have been reluctant to accept day old mice whilst readily accepting pre-weaner mice. The average sized hatchling Taipan is quite capable of eating a mouse up to 10gm in weight. Unlike the snap and release action of the adult snakes, the young attain a firm grip on the mice. This action may continue for a month or so when it changes to the snap and release method.

With few exceptions, the young snakes have been exceptionally good feeders once offered the larger mice. Force feeding had to be applied to the occasional undersized young but generally only for a short period.

Coastal Taipan: Growth

Growth can be extremely rapid and it was quite common for my specimens to exceed 1.7 metres (total) at 12 months of age and 2.1m at 24 months of age.

The following tables relate to the growth of one individual over a three year period. All food was weighed before it was offered as a feed. The snake was measured at regular periods over the first 14 months and less regularly over the latter period. The snake was starved for a short period before weighing to ensure accurate body weights. The number of sloughs and the period between them were also recorded.

The Coastal Taipan, Oxyuranus scutellatus, is the largest species from the elapid family of snakes in Australia. Some texts say it grows to over 300cm. Worrell (1963), for example, notes, “. . . Length may exceed ten feet; six feet is average”. However, none of the many specimens held in museum collections in Australia exceeds 300 cm.

The Coastal Taipan, Oxyuranus scutellatus, is the largest species from the elapid family of snakes in Australia. Some texts say it grows to over 300cm. Worrell (1963), for example, notes, “. . . Length may exceed ten feet; six feet is average”. However, none of the many specimens held in museum collections in Australia exceeds 300 cm.

Professor Rick Shine, University of Sydney, measured all the Coastal Taipans in museum collections in the early 1980s. The largest one, a male, had a snoutvent length of 226 cm. This would have a total length of about 260 cm. No new extra-large Coastal Taipans were lodged in Australian museum research collections untill ‘Terrence’ died.

Terrence was the ‘pet’ of Joe Sambono Jnr, a friend to herpetologists from the Queensland Museum. Terrence, with a snout-vent length of 242.5 cm and a total length of 290 cm, died after seven and a half years in captivity. He had been raised ‘out of the egg’, by Joe. Joe was very sad that Terrence had died. However, Joe’s curatorial friends at the Museum were elated to receive such a large specimen, when one was needed for the public display programme. When Terrence died, he weighed 6.2 kg. At 290 cm, he was the largest Coastal Taipan whose length was measured, not just estimated. The measurement can be checked by anyone interested, because the specimen is in the research collection of the Queensland Museum.

At the Queensland Museum, Terrence was moulded and cast in a life-like pose for display. The cast, painted in exquisite detail by museum preparator Alison Hill, is now a feature of the exhibition, “Wildlife of Cape York Peninsula”. This can be seen in the Cooktown Interpretive Centre, overlooking the restored, historic botanic gardens in Cooktown, north-eastern Queensland.

At the Queensland Museum, Terrence was moulded and cast in a life-like pose for display. The cast, painted in exquisite detail by museum preparator Alison Hill, is now a feature of the exhibition, “Wildlife of Cape York Peninsula”. This can be seen in the Cooktown Interpretive Centre, overlooking the restored, historic botanic gardens in Cooktown, north-eastern Queensland.

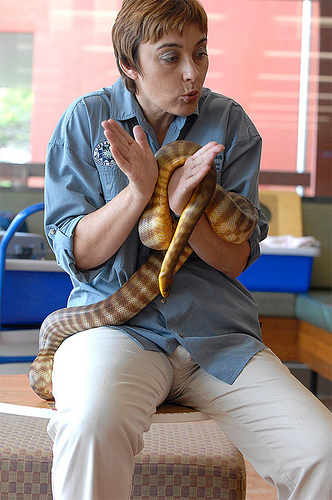

The Victorian Herpetological Society would like to thank the owner of the snake, Joe Sambono (pictured here with Terrence), the photographer, Simon Fearn and the Queensland Museum for allowing us to use material from their site.

The taipan is one that was bred by Brian Barnett and supplied to Joe Sambono.

Acknowledgments

Keith Day ‘introduced’ me to the Taipan many years ago when I lived in Queensland. Roy Pails of Ballarat loaned me one of the breeding males when requested. Chris Banks of the Royal Melbourne Zoo gave advice when asked. Bruce and Keiron Howlett retyped the manuscript at short notice. I particularly thank my family Lani, Brett and Ty who have given up so much to allow me to pursue my interests in herpetology to such a degree.

Literature Cited

Banks, C.B. 1983. Breeding the Taipan at the Royal Melbourne Zoo. International Zoo Yearbook. 23.

Barnett, B.F. 1978. Taipan. Newsletter of the Victorian Herpetological Society, 9:16-20.

Barnett, B.F. 1980. Captive breeding and a novel egg incubation technique of the Children’s Python (Liasis childreni). Herpetofauna 11(2):15-18.

Barnett, B.F. 1981 Artificial incubation of snake eggs. Monitor 1(2):31-39.

Cogger, H.G. 1983 Reptiles and Amphibians of Australia (Revised Edition) A.H. and A.W. Reed. Sydney.

Peters, U. (1973) Breeding of the Taipan (Oxyuranus scutellatus) in captivity. Bull. Zoo Man. 4(1):7-9.

Shine, R. and J. Covacevich (1983) Ecology of highly venomous snakes: the Australian genus Oxyuranus (Elapidae). Journal of Herpetology, 17:60-69.

Table Results (images):

Table 1A-1B and Table 2

Table 3 and Table 4

Table 5 and Table 6

The Coastal Taipan is a hardy snake in captivity and provided due respect is given to this extremely alert snake no unusual problems should be encountered.