Try Some Tree Frogs

/By Gerold, Cindy and Walter Merker

Tree frogs can offer entertainment and enjoyment - and, of course, challenge.

From the dry Gran Chaco region of South America to the icy waters of Alaska, frogs and toads have been found in nearly every environment. With nearly 4,000 species - more than 10 times the number of salamander and newt species - anurans are by far the most successful group of the amphibians.

The reason behind this success is that amphibians are the primary vertebrate consumers of invertebrates in many freshwater and moist terrestrial environments (Stebbins and Cohen, 1995). Although salamanders and caecilians also fall within this description, they are not able to survive in the variety of environments that anurans can. For instance, not many have adapted to arboreal environments. Only the climbing salamanders (Aniedes spp.) of North America and the palm salamanders (Bolitoglossa spp.) of tropical Central and South America have done so. The fact that more than 600 anuran species have successfully adapted to arboreal environments accounts for a portion of the vast discrepancy between the numbers of frogs versus the number of salamanders.

Tree frogs have many unique adaptations that have allowed them to become successful in their lofty environment. These adaptations include forms of predator evasion, pursuance of and capture of food, and reproduction. There are many tree frogs (family Hylidae) found around the world.

Tree frogs have many unique adaptations that have allowed them to become successful in their lofty environment. These adaptations include forms of predator evasion, pursuance of and capture of food, and reproduction. There are many tree frogs (family Hylidae) found around the world.

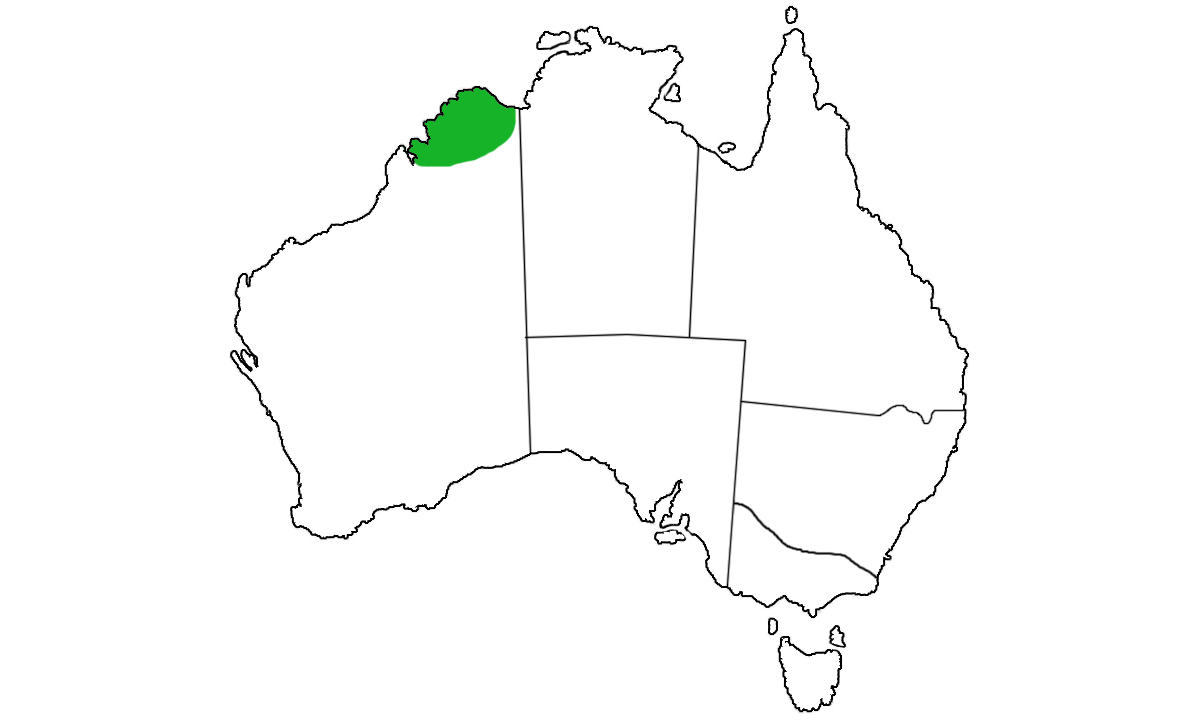

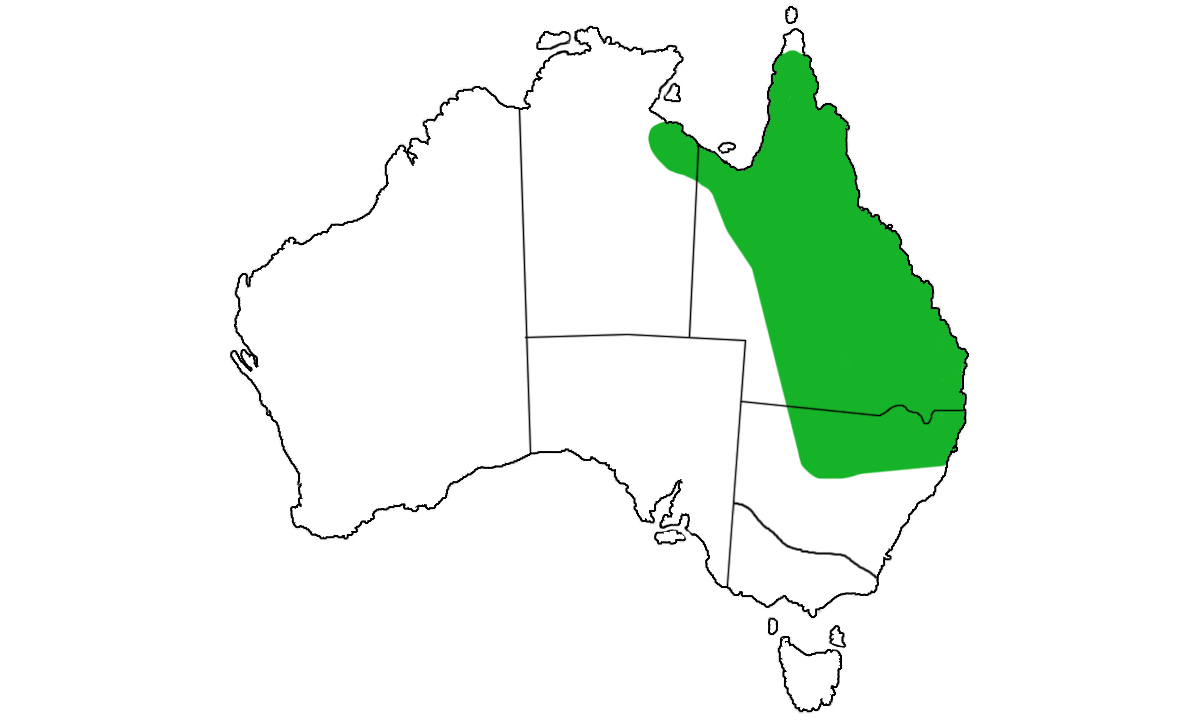

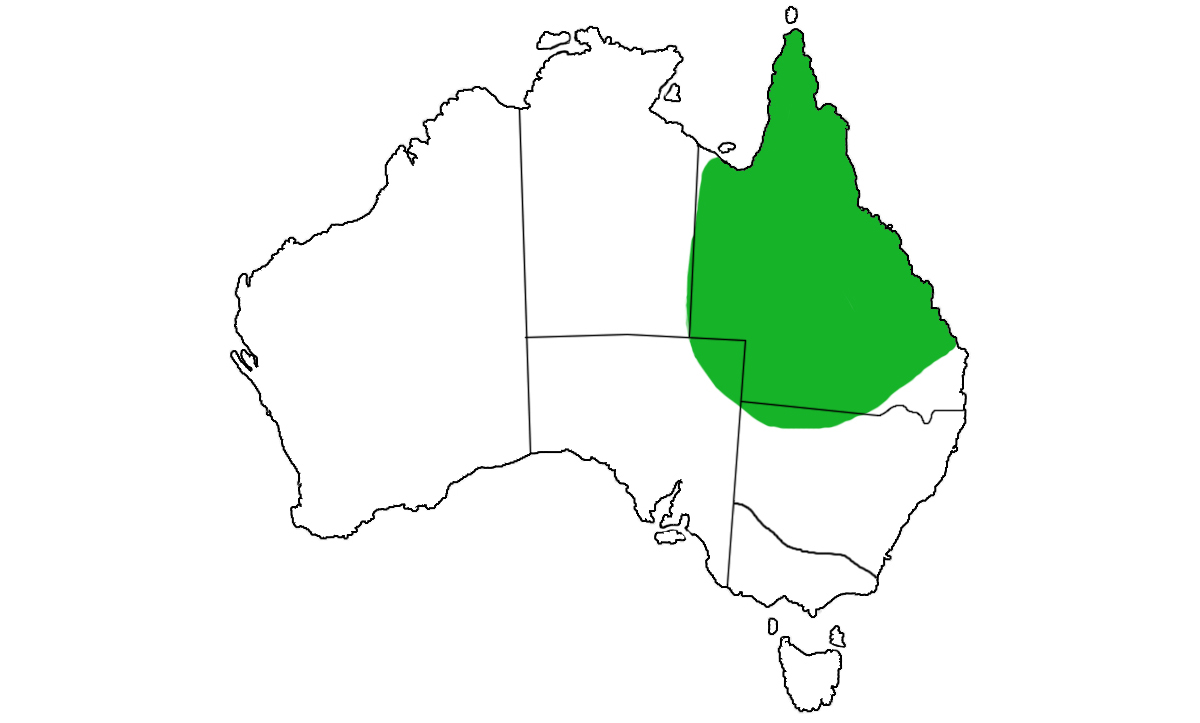

Old World tree frogs include gliding tree frogs, such as the Chinese gliding tree frog (Rhacophorus dennysi), as well as various members of the family Hylidae. The subfamily Peloryadinae is found in Australia and Indonesia, and it includes species such as White's tree frog (Litoria caerulea).

The New World is also home to many unique members of the family Hylidae. Their numbers include the Phyllomedusines, which are know for the photogenic red-eyed leaf frog (Agalychnis callidryas), the bizarre casque-headed tree frogs (Trachycephalus, Triprion and the monotypic genus Pternohyla) and the marsupial frogs (Gastrotheca and Hemiphractus spp.) as well as many of the typical Hyline tree frogs.

The number and variety of tree frogs found in the pet industry has increased dramatically in the last few years, and many unusual frogs have been bred under captive conditions. Hopefully this trend will continue, and captive reproduction will promote the future success of this fascinating group of amphibians.

Tree Frogs: The Captive Care

Maintenance of captive amphibians is inherently different from that of the reptiles. Because amphibians' skin does not prevent the loss of water, a controlled humidity level inside the enclosure is central to their survival. Also, amphibian skin is very permeable, so providing a captive environment that is free of harmful pathogens and chemicals is vital.

Maintenance of captive amphibians is inherently different from that of the reptiles. Because amphibians' skin does not prevent the loss of water, a controlled humidity level inside the enclosure is central to their survival. Also, amphibian skin is very permeable, so providing a captive environment that is free of harmful pathogens and chemicals is vital.

Failure to adhere to strict measures of cleanliness frequently results in shortened life spans for captive amphibians. Tree frogs are best kept in cages that are easy to clean. They enjoy tall vivaria that allow them to roost high above the cage floor during the day. A screened lid will help with ventilation, and a secure lid is vital. If frog escapes from its cage, it quickly falls victim to desiccation, perhaps in less than a day, for it is rare that a frog is able to find a place humid enough to allow for its survival.

If you locate an escaped frog but it has become desiccated, place the animal in a shallow bowl of spring water, tipping it slightly so that the head of the frog is not immersed. With a little luck, the animal will still have the strength to reabsorb the water it has lost and will survive. Do not rush to conclusions about the likelihood of survival; we have had a desiccated frog lie motionless in a bowl of water for more than a n hour and still make a full recovery.

Caging Options

Amphibian keepers often use naturalistic vivaria because they are aesthetically pleasing. However, cleaning a naturalistic cage is much more problematic than maintaining frogs under more sterile conditions. We use very simple caging with damp paper towels as a substrate. Paper towels allow a cage to be monitored easily for waste build-up. We recommend unbleached paper towels for captive maintenance of amphibians, but have used white paper towels for many years without problems. White paper towels will also allow you to easily gauge the cleanliness of an enclosure.

Amphibian keepers often use naturalistic vivaria because they are aesthetically pleasing. However, cleaning a naturalistic cage is much more problematic than maintaining frogs under more sterile conditions. We use very simple caging with damp paper towels as a substrate. Paper towels allow a cage to be monitored easily for waste build-up. We recommend unbleached paper towels for captive maintenance of amphibians, but have used white paper towels for many years without problems. White paper towels will also allow you to easily gauge the cleanliness of an enclosure.

Place three layers of paper towels on the base of the cage, then saturate them with spring water. Avoid distilled water completely. When distilled water is concentrated on the outside of an animal whose internal structure contains various compounds (minerals, electrolytes and such), simple diffusion, or osmosis, results in a lethal level of bloating. Spring water does not create this difference in water concentration.

We place a living plant in the cage with several of our tree frogs to provide hiding place. Keep the plant in a planter so you can easily remove it to wipe down the leaves and the outside of the planter, to remove feces or other debris. Once you have cleaned the enclosure and added new paper toweling, return the plant. A branch or a length of PVC pipe can also be placed in the cage, on which the larger frogs can roost during the day. This also can be washed when the enclosure is cleaned. Temperature

In general, frogs require lower enclosure temperatures compared to reptiles. We usually maintain a background temperature of 73 degrees Fahrenheit for our anurans. Our temperate tree frogs are maintained at room temperature with no supplemental heating. Tropical species are provided with an undertank heater in order to ensure that they have optimal humidity and a slightly higher temperature. Using heat tapes requires much more careful monitoring of the cage substrate to ensure that it does not become too dry.

In general, frogs require lower enclosure temperatures compared to reptiles. We usually maintain a background temperature of 73 degrees Fahrenheit for our anurans. Our temperate tree frogs are maintained at room temperature with no supplemental heating. Tropical species are provided with an undertank heater in order to ensure that they have optimal humidity and a slightly higher temperature. Using heat tapes requires much more careful monitoring of the cage substrate to ensure that it does not become too dry.

Some animals, such as Chacoan monkey tree frogs (Phyllomedusa sauvagii) and African gray tree frogs (Chiromantis xerampelina), should be provided with a heat lamp for basking. The basking site should reach an optimal temperature of 90 degrees. We have found that if frogs are kept too cool they do not digest their food properly and slowly lose body mass.

Lighting

The use of full-spectrum lighting over the top of the cage may be beneficial to tree frogs. In the wild, these animals bask occasionally, sitting atop the substrate or plants in which they generally hide. At the very least, full-spectrum lighting keeps the plants healthy and also brings out the best color in animals.

We have used several different full-spectrum fluorescent lights with good results. These light also do not generate the heat of an incandescent light and o not accelerate the loss of moisture in the cage.

We have used several different full-spectrum fluorescent lights with good results. These light also do not generate the heat of an incandescent light and o not accelerate the loss of moisture in the cage.

Feeding

Feeding tree frogs is usually very easy. Frogs are cued to feed on anything that moves, and tree frogs are no exception. Many tree frog species have a high metabolic rate and have to eat several times weekly to maintain proper body mass. Failure to feed the frog enough will result in dramatic weight loss and, eventually, death.

We offer our frogs a cricket-based diet. The crickets are approximately the same length as the width of the frog's head. Any larger and our frog experience difficulties during feeding. Before we feed them to our amphibians, our crickets are "super charged" on a diet of a monkey chow, orange slices and various vegetables, including potatoes, red-leaf lettuce and carrots.

We also dust the crickets with a calcium/mineral supplement once or twice weekly. Crickets are placed into a large plastic cup with supplement in the bottom. We leave the crickets in this cup for several minutes so that they pick up some of the powder on their bodies, then place the crickets in feeding bowls. Although feeding bowls prevent the crickets from soiling the paper toweling, if not properly maintained they can be a health risk to the frogs. Wash the bowl after feeding to prevent buildup of supplement on the bottom of the container, which may allow the frogs to absorb an excess vitamins and minerals. This directly affects the kidneys and, ultimately their ability to metabolize.

We occasionally offer other food items, as well. Silk moth larvae are a wonderful alternative. Because these larvae feed on mulberry feeds, which are naturally high in calcium, they provide an excellent source of this vital nutrient. Silk moth larvae are easy to rear and are offered for sale by several companies around the country. They range in size from approximately pinhead-cricket size up to the mass of about 100 adult crickets.

We occasionally offer other food items, as well. Silk moth larvae are a wonderful alternative. Because these larvae feed on mulberry feeds, which are naturally high in calcium, they provide an excellent source of this vital nutrient. Silk moth larvae are easy to rear and are offered for sale by several companies around the country. They range in size from approximately pinhead-cricket size up to the mass of about 100 adult crickets.

We also offer wax moths and their larvae. These must be offered only as part of a varied diet because they are high in fat. Frogs will quickly become obese if they are fed too many wax moth larvae. Our smaller anurans are also fed wingless fruit flies (Drosophila). Fruit trees are easily obtainable and are important because they are swallowed easily and can be eaten in large quantities. Health Concerns

Frogs are susceptible to many different diseases and pathogens. Because of their delicate skin, frogs need to be maintained at the utmost level of cleanliness. Because amphibians do not have the disease-resistant skin of a reptile (or you, for that matter), a frog can be invaded easily by pathogens. This is a double-edged sword when it comes to medicating frogs.

Although medications can be placed on the surface of the skin and absorbed by the frog, dosage can be problematic. This may not be a serious problem with less-deleterious drugs. When an accurate dosage is required, it is better to place the medication directly in the frog's gullet. This is accomplished with the aid of a tuberculin syringe for larger frogs and a feeding tube for smaller, more delicate frogs.

Internal parasites are found in many captive frogs, especially if the animals are wild caught. The recommended treatment for internal protozoans is metronidazole (Flagella). Fenbendazole (Panacur) is recognized as the best treatment for nematodes. As with any sick animal, assistance from a qualified veterinarian is helpful for successful treatment of a parasitized frog.

Cage Cleaning

Again, cleanliness is crucial. Usually, we completely clean our frog terrariums every two to three weeks. We spot clean for feces between complete cage cleanings. How thoroughly we clean the enclosures depends entirely on two things: the number of frogs in the cage and how dirty certain animals are. Some species foul their areas more quickly than others. One soon learns how often cages need attention. Because most tree frogs climb the sides of the terrarium, the entire cage must be scrubbed and rinsed thoroughly.

Again, cleanliness is crucial. Usually, we completely clean our frog terrariums every two to three weeks. We spot clean for feces between complete cage cleanings. How thoroughly we clean the enclosures depends entirely on two things: the number of frogs in the cage and how dirty certain animals are. Some species foul their areas more quickly than others. One soon learns how often cages need attention. Because most tree frogs climb the sides of the terrarium, the entire cage must be scrubbed and rinsed thoroughly.

When Cleaning, frogs can be handled safely by using latex gloves moistened with spring water. This will prevent any pathogens form entering the frogs by way of human skin to frog skin contact. Then the frogs are placed in sterile holding containers so that they are not restrained for any length of time. These containers are usually half-gallon, properly ventilated plastic jars. These holding containers are cleaned after each use.

Overall, the handling of frogs should be kept to a minimum to prevent unnecessary exposure to disease and stress, as well as injury that could result from frogs hopping out of their caretakers' hands.

North American Tree Frogs

The name "tree frog" is applied to a wide variety of species found worldwide. Many of these forms are found in pet stores or on the tables of many vendors at the various reptile and amphibian shows around the country.

The name "tree frog" is applied to a wide variety of species found worldwide. Many of these forms are found in pet stores or on the tables of many vendors at the various reptile and amphibian shows around the country.

The United States is home to many beautiful and interesting types of of tree frogs. Most of these species belong to one of the two genera: Hyla and Pseudacris. Pseudacris is rarely seen in pet trade. Some of the most common varieties of North American tree frogs offered for sale include the green tree frog (Hyla cinerea), the gray tree frog (H. versicolor) and the barking tree frog (H. gratiosa).

We have maintained these three common species for many years on a very simple caging and feeding regime. We keep our more common North American tree frogs in simplistic enclosures. We use caging that is taller than those used for some of our other amphibians, with damp paper towels as substrate. Plants, such as Pothos, can be placed in these cages to provide the animals perch sites and cover. These frogs will climb the sides of their terrariums and sleep on the glass if no plants are provided.

Their diet is cricket-based, but occasionally supplemented by silk moth larvae. Our North American tree frogs are fed every third day. Each animal is fed 3 to 5 crickets that are approximately the same length as the width of the frog's mouth or smaller.

Although the green, gray and barking tree frogs are the most common North American tree frogs seen in pet trade. we have also had great success with some of the less frequently seen tree frogs, such as the Pacific tree frog (Hyla regilla), the California tree frog (H. cadaverina) and the mountain tree frog (H. eximia), using the strategies mentioned above.

Central and South American Tree Frogs

Central and South America are home to nearly 44 percent of anuran species (Cohen and Stebbins, 1995). Many tree frogs inhabit this region, and some are truly exquisite. Numerous species from several genera, including Hyla, Phyllomedusa, Agalychnis and Smilisca, are often offered for sale, including many captive-bred specimens.

Central and South America are home to nearly 44 percent of anuran species (Cohen and Stebbins, 1995). Many tree frogs inhabit this region, and some are truly exquisite. Numerous species from several genera, including Hyla, Phyllomedusa, Agalychnis and Smilisca, are often offered for sale, including many captive-bred specimens.

We maintain several varieties of tropical Hyline frogs and Phyllomedusine frogs in 10-, 15-, or 20-gallon tall enclosures. We supply many of our tropical tree frogs with undercage heating by placing a heating element beneath a small portion of their cages. This is important to properly maintain temperatures to aid proper digestion. Ensure that the substrate in the cage does not dry out because of this additional heat source; you may need to moisten the paper towel substrate once or twice a day. We also keep a shallow dish of spring water in some cages to allow the animals to rehydrate should the need arise.

Many of our smaller frogs, such as the orange-sided monkey frog (Phyllomedusa hypocondrialis) and the tiger-striped leaf frog (P. tomopterna), are provided perching and hiding sited via hydroponically grown Pothos. We usually feed them every third day, as we do with our North American tree frogs. Because many of these animals are quite large, such as the giant monkey tree frog (P. bicolor), they can be fed larger food items. We feed our adult giant monkey tree frogs 5 to 6 adult crickets or 3 large silk moth larvae per meal. Supplementation is provided to these frogs on the same regimen as previously mentioned.

Many of the Central and South American tree frogs make outstanding candidates for naturalistic cages. the red-eyed tree frog (Agalychnis callidryas) and several varieties of the monkey frogs (Phyllomedusa spp.) make superior display animals in a nicely planted enclosure adorned with tropical plants. If you decided to try a naturalistic approach, be sure to use wide-spectrum lighting not only for the animals, but for the plants as well.

Some monkey tree frogs, such as the Chacoan monkey frog (Phyllomedusa sauvaugii), will benefit from exposure to the sun for a few hours once a week. Use a screen cage (not glass) and ensure that the animal has access to water and shade should it become overheated. This type of frog actually basks in the sun; it has the ability to produce a lipid which it smears over its body to prevent desiccation. This is a necessary adaptation for survival in the arid Gran Chaco region of South America.

Old World And Australian Tree Frogs

Numerous tree frog species found in other parts of the world are frequently offered for sale. Perhaps the most common is White's tree frog (Litoria caerulea). These natives of Indonesia and Australia have been bred under captive conditions for many generations, and many of the bright green or blue animals attain lengths of up to 5 inches. These frogs can eat a lot and may become obese if permitted to do so. They do well in either a simple cage or a naturalistic enclosure. We prefer to keep our White's tree frogs in fairly large enclosures to encourage exercise, thus reducing the likelihood of obesity.

Numerous tree frog species found in other parts of the world are frequently offered for sale. Perhaps the most common is White's tree frog (Litoria caerulea). These natives of Indonesia and Australia have been bred under captive conditions for many generations, and many of the bright green or blue animals attain lengths of up to 5 inches. These frogs can eat a lot and may become obese if permitted to do so. They do well in either a simple cage or a naturalistic enclosure. We prefer to keep our White's tree frogs in fairly large enclosures to encourage exercise, thus reducing the likelihood of obesity.

Interesting frogs found in other regions of the world include some of the gliding tree frogs of the genus Rhacophorus. We have worked with two varieties of these animals over the years, including the blue-webbed gliding tree frog (Rhacophorus reinwardtii) and the Chinese gliding tree frog (R. denysi). They do exceptionally well and have on occasion been captively bred. Gliding tree frogs are quite large. They have the ability to "parachute" or glide, so it is imperative to provide them with tall, spacious enclosures. They should be fed crickets as the base diet. Larger frogs can be fed up to 5 adult crickets per meal every third day. As with all the frogs mentioned in this article, food items should be dusted with a calcium and vitamin supplement once a week before offering it.

Frogs In Your Future?

Frogs are both beautiful and interesting; however, they tend to be fairly time-consuming as terrariumn pets go. Also, if they become ill or simply never thrive, it can be difficult to diagnose the problem. On the other hand, healthy frogs can become long-term captives. Some of ours have been in captivity for more than 10 years. Those frogs hatched in captivity tend to do comparatively better than wild-caught individuals. However, once de-parasitized and de-stressed, wild-caught individuals can also live many years in a collection.

Frogs are both beautiful and interesting; however, they tend to be fairly time-consuming as terrariumn pets go. Also, if they become ill or simply never thrive, it can be difficult to diagnose the problem. On the other hand, healthy frogs can become long-term captives. Some of ours have been in captivity for more than 10 years. Those frogs hatched in captivity tend to do comparatively better than wild-caught individuals. However, once de-parasitized and de-stressed, wild-caught individuals can also live many years in a collection.

For the person who enjoys caring for the frogs, nothing is more spectacular than walking into a room occupied by these dazzling creatures, no matter their origins. Sitting or lying in bed in the evening listening to the chorus of the males transports the fortunate listener to a far-away land.

References:

Cohen, Nathan W. and Robert C. Stebbins. 1995. A Natural History of Amphibians. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ. Tree Frogs - green and beautiful.