Long considered your best bet if you're a beginner, leopards and beardies remain favorite pets.

By Joe Hiduke and Bill Brant

Younger readers of reptiles may be surprised to know that few captive-bred lizards have been available in the recent past. While there are far more species and specimens available now than there ever have been, those species, that have been with us the longest are still among the best pet reptiles.

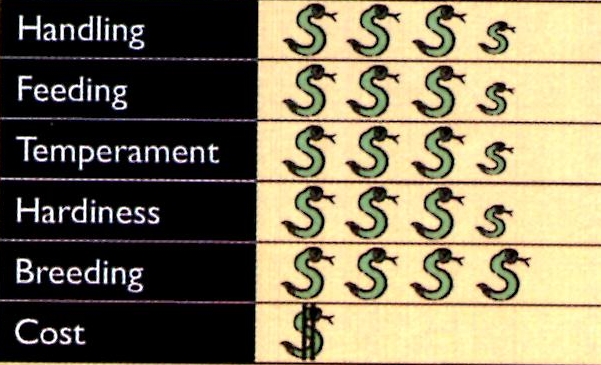

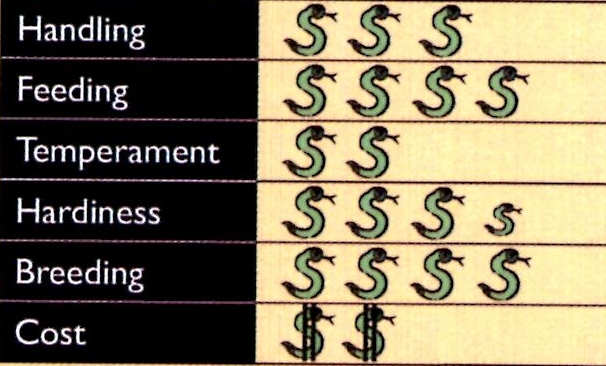

Leopard geckos (Eublepharis macularius) and beardies (Pogona vitticeps) rank among the most popular pet reptiles. Both species are easy to care for, personable, and readily available. Leopard geckos are often the choice for a first pet reptile. Their popularity as a starter herp is due primarily to their inexpensive nature and because they do not require much in the way of equipment to be properly maintained.

Leopard geckos (Eublepharis macularius) and beardies (Pogona vitticeps) rank among the most popular pet reptiles. Both species are easy to care for, personable, and readily available. Leopard geckos are often the choice for a first pet reptile. Their popularity as a starter herp is due primarily to their inexpensive nature and because they do not require much in the way of equipment to be properly maintained.

Beardies are more expensive and require larger, more elaborate enclosures; however, beardies tend to reward their owners with a much higher degree of interaction.

LEOPARD GECKOS

By a large margin, more leopard geckos are captive bred in the United States than any other reptilian species.

In addition, for reasons already given, leopards enjoy mass appeal, in part because they come in a wide variety of color and pattern morphs. Some of these are selectively bred, such as high-yellows, tangerines, and melanistics. Other morphs are genetic mutations, including albinos, patternless, blizzards and jungles. Combinations of all the above are also produced.

All leopard gecko genetic mutations are thought to be single gene traits that breed true, but there are multiple strains of albinos that will produce normals when bred together. This is a relatively new area in gecko production and certainly more surprises are on the horizon. Regardless of appearance, all of these geckos have the same captive-care requirements.

All leopard gecko genetic mutations are thought to be single gene traits that breed true, but there are multiple strains of albinos that will produce normals when bred together. This is a relatively new area in gecko production and certainly more surprises are on the horizon. Regardless of appearance, all of these geckos have the same captive-care requirements.

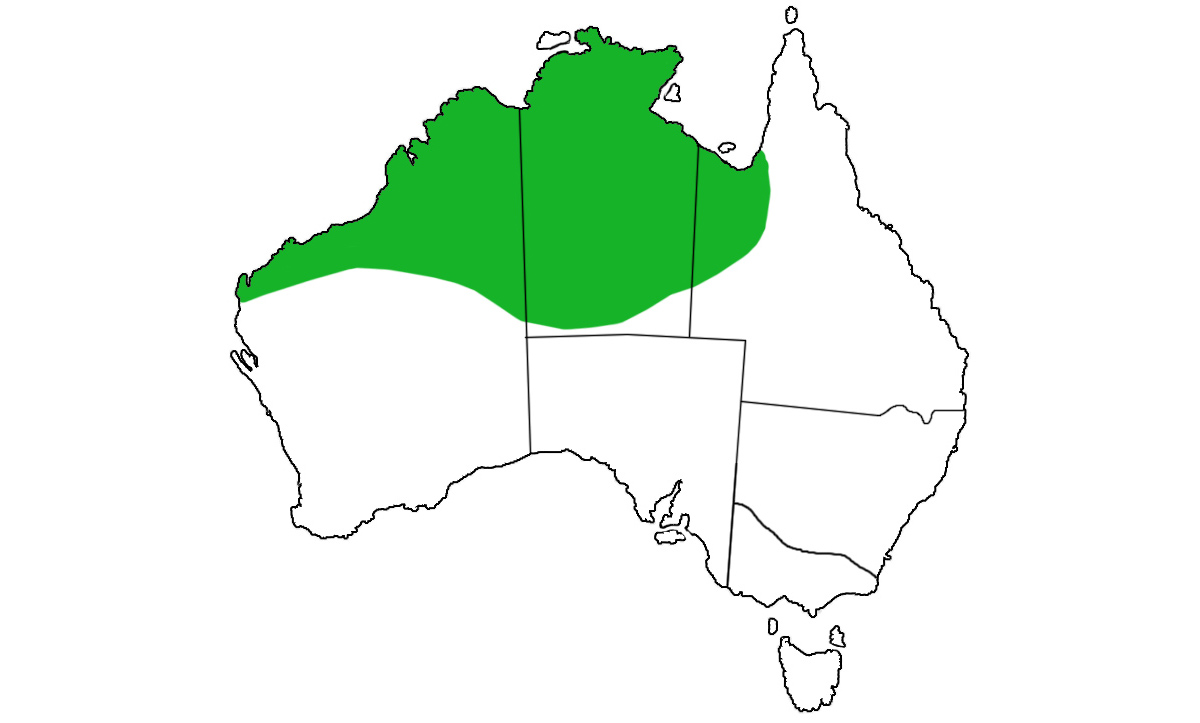

The range of leopard geckos encompasses Pakistan, Afghanistan and western India. Almost all animals available today are captive bred, and imports should be avoided by novices. In their native environment, leopards frequent arid areas and are thought to live in loose colonies with considerable cover.

There are several options available for acquiring geckos, including pet shops, breeders and reptile expos. First-time buyers should search for a gecko locally so they can see what they are buying. When selecting a gecko, choose an animal that is alert, active and with a full tail. The tail should expand past the base; geckos with a thin tail may be in poor health.

Hatchling-sized geckos are less expensive and more commonly available. However, they tend to be high-strung and fragile. Until they put on some size, hatchlings should be rarely handled. Sub-adults are very sturdy and are ideal to start with, but they will be more expensive.

Hatchling-sized geckos are less expensive and more commonly available. However, they tend to be high-strung and fragile. Until they put on some size, hatchlings should be rarely handled. Sub-adults are very sturdy and are ideal to start with, but they will be more expensive.

If you maintain multiple reptiles, you should always quarantine new arrivals away from existing collection, service them last and use separate equipment. Three months is a reasonable quarantine time; however, some breeders quarantine for up to a year.

Housing Leopards

Housing for leopard geckos can range from plastic shoeboxes to large, elaborate vivariums. Single animals do well in a 10-gallon tank, while a trio can easily be housed in a standard 20-gallon, "long" aquarium. A secure lid is essential. While leopard geckos don't climb glass, they can climb furnishings quite well, and household pets, (such as cats) would love to eat them. Leopard gecko breeders often house there geckos in plastic sweater boxes in rack systems.

The specifics of the cage are not critical, as long as the animal's needs can be properly met. Multiple geckos can be kept together, but do not keep more than one mature male to a cage. Males will fight and can have been known to kill one another.

The substrate is an important consideration. Newspaper is an excellent choice, albeit aesthetically displeasing. Other options include calcium or silica based sand with a fine consistency, mulch, bark chips or cage carpet. It has been said that sand can cause impactions, but if the geckos' nutritional needs are met they are not likely to ingest sand to cause a problem. Small bark chips can become impacted, but using large-chip substrate eliminates this risk. Cage carpets must not have any loose strands because these tend to wrap around gecko feet or legs and can lead to necrosis.

The substrate is an important consideration. Newspaper is an excellent choice, albeit aesthetically displeasing. Other options include calcium or silica based sand with a fine consistency, mulch, bark chips or cage carpet. It has been said that sand can cause impactions, but if the geckos' nutritional needs are met they are not likely to ingest sand to cause a problem. Small bark chips can become impacted, but using large-chip substrate eliminates this risk. Cage carpets must not have any loose strands because these tend to wrap around gecko feet or legs and can lead to necrosis.

Thermal Gradients

As for all ectotherms, a proper thermal gradient is essential for leopard geckos. They are nocturnal, hence a basking lamp is completely inappropriate. An under-tank heating pad designed for reptiles is the best option. If placed at one end of the cage, this creates a thermal gradient from one end of the cage to the other.

If you use newspaper as a substrate, use caution when using a heating pad; some brands need a deeper substrate to disperse heat, and thermal burns are likely if the enclosure glass gets too hot. We don't recommend heat rocks because they do not provide a gradient.

Ideal leopard gecko cage temperatures are about 95 degrees Fahrenheit at the warm end and the low 80s at the cooler end.

Hide and Seek

Hide areas are important fixtures for any gecko cage. Rock caves, cork hollows, or plastic shoeboxes are all options. These should be provided at both the warm and cool ends of the enclosure, Hide areas need to be large enough to encompass a heat gradient. Use caution when creating a hide area from rocks, as geckos tend to dig and can collapse rock piles with fatal consequences. If you have a natural vivarium, the structures should be siliconed in place.

Hide boxes may also be used to provide a high-humidity area. While leopard geckos come from arid areas, they are still thought to inhabit high-humidity microclimates in their burrows. Even in Florida, captive leopard geckos may experience dry sheds if kept without a humid hide box. Damp vermiculite or sphagnum moss works well to raise the humidity inside a hide box.

Beardies and Leopards: Diet and Nutrition

For the reptile enthusiast with snake experience, gecko nutrition is a whole new challenge. They are insectivores and must have a high-quality diet if they are to thrive. Geckos do well on a diet of mealworms, and can also be given crickets, superworms, wax worms, and pinky mice. Offer your pet leopards as much variety as possible.

For the reptile enthusiast with snake experience, gecko nutrition is a whole new challenge. They are insectivores and must have a high-quality diet if they are to thrive. Geckos do well on a diet of mealworms, and can also be given crickets, superworms, wax worms, and pinky mice. Offer your pet leopards as much variety as possible.

Feeder insects must also be fed a quality diet before being fed to your geckos. Lizards receive much of the nutrition from the gut content of their prey. There are many quality commercial insect foods available; these should be supplemented with fresh fruits and veggies for added moisture. Additionally, your geckos' prey should be dusted with a vitamin and mineral supplement several times a week for juveniles, less often for adults. The supplement should contain calcium and phosphorous in at least a 2-1 ratio, high levels of vitamin A, high amounts of D3 and a wide range of other vitamins.

Geckos can be given free access to mealworms. Because loose mealworms will dig into the substrate, place them in a bowl they cannot escape from. Any supplements on the worms will fall off after a couple of hours, so the bowl should contain a shallow layer of food (not enough to cover the worms) to keep their digestive tracts full. Not all geckos will readily accept mealworms, so you will have to monitor the condition of the geckos.

Crickets are also a good dietary component. Hatchling geckos can be fed crickets daily, while sub-adults and adults can be fed every other day. Don't feed any geckos more than they will eat overnight -- squads of uneaten crickets have been known to chew holes in leopard geckos. The crickets should be dusted with a supplement at every feeding for hatchlings and once a week for adults.

Many geckos will also accept superworms as a regular part of their diet. Wax worms are another good supplement but very fatty and should be used sparingly. Pinky mice are another good supplement, but again they should be offered in moderation.

Fresh water must always be available. Hatchling geckos may not drink from bowls and are very prone to dehydration, so they must be sprayed down a couple of times a day until they are drinking on their own.

Breeding Leopards

Many hobbyists who keep leopard geckos eventually become interested in breeding them. Geckos can be bred in a 1-1 ratio up to (at least) a 1-20 ratio of males to females. Remember, only one male per cage.

Many hobbyists who keep leopard geckos eventually become interested in breeding them. Geckos can be bred in a 1-1 ratio up to (at least) a 1-20 ratio of males to females. Remember, only one male per cage.

The first step in any successful breeding endeavor is to make sure that your two breeders are indeed a pair. Adult males are easily identified by their hemipenal bulges, immediately caudal to the cloaca, and the V-shaped row of pre-anal pores just cranial to the cloaca. These can be seen in juvenile geckos but are not well developed until maturity is reached.

Maturity is a function of size, not age, in leopard geckos. A safe breeding size 1.4 ounces, but if raised in mixed-sex cages leopards will breed when they're as small as 0.7 ounces. This frequently leads to serious health problems for the females, however, so growing animals should be separated by sex. Most leopard geckos will reach breeding size when they're about 1 year old.

Many breeders put their geckos through a winter cooling period. This is recommended but not required, with a minor cooling period not lower than 70 degrees Fahrenheit for one to three months. Food should be made available, and the geckos' consumption will decrease over time. During cool-down, males can be kept in breeding groups or separately.

In the springtime, raise the temperature to initiate breeding activity, and reintroduce the males to the females. Breeding generally occurs shortly after they have warmed up.

Females lay clutches of two eggs in a damp nest box at approximately 30-day intervals for around six months. This is a stressful time for females, and they must be closely monitored to make sure they are keeping adequate body weight. This is a good time to add wax worms or pinkies to their diet.

Eggs should be incubated in plastic boxes with a damp medium and little airflow. Vermiculite or perlite in a 1-1 ratio with water (measure by weight) works well as an incubation medium. Incubation temperatures often determine the sex of the offspring and also may impact adult behavior. Temperatures in the low 80s will yield a mix of sexes in the hatchlings. At these temperatures, the eggs should hatch in about 45 days.

Neonates will shed and be ready to start feeding in a day or two. Potential health problems to be wary of include dry sheds, abscesses, injury from cage-mates, nutritional imbalances and internal parasites.

It is important to work with a knowledgeable reptile veterinarian, as reptile medicine is a new and frequently changing discipline. The Association of Reptile and Veterinarians (www.arav.org) is a good source for locating knowledgeable vets. Due to the low cost of leopard geckos, many people tend to view them as disposable pets and refuse to provide proper veterinary care. If this is your attitude, please do not purchase a leopard gecko.

BEARDIES

Bearded dragons (Pogona vitticeps) are Australian agamids. They are a relatively recent addition to the United States pet trade and have become well established due to their hardiness, social behaviors and prolific breeding habits.

Bearded dragons (Pogona vitticeps) are Australian agamids. They are a relatively recent addition to the United States pet trade and have become well established due to their hardiness, social behaviors and prolific breeding habits.

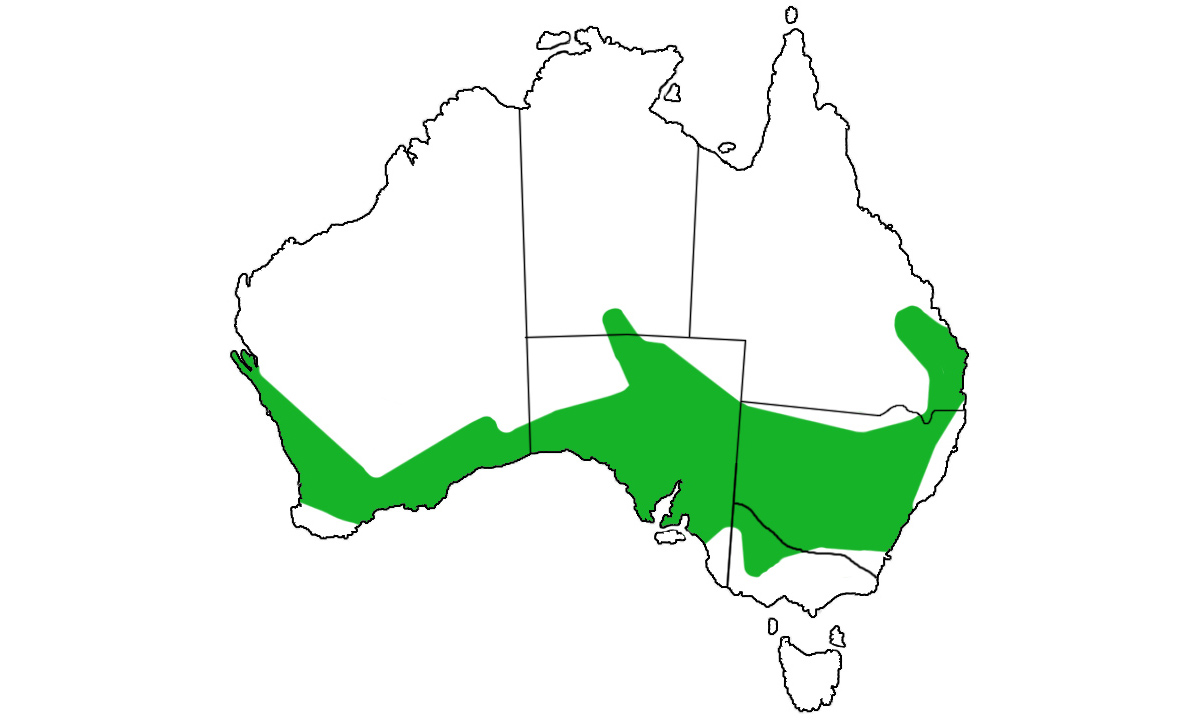

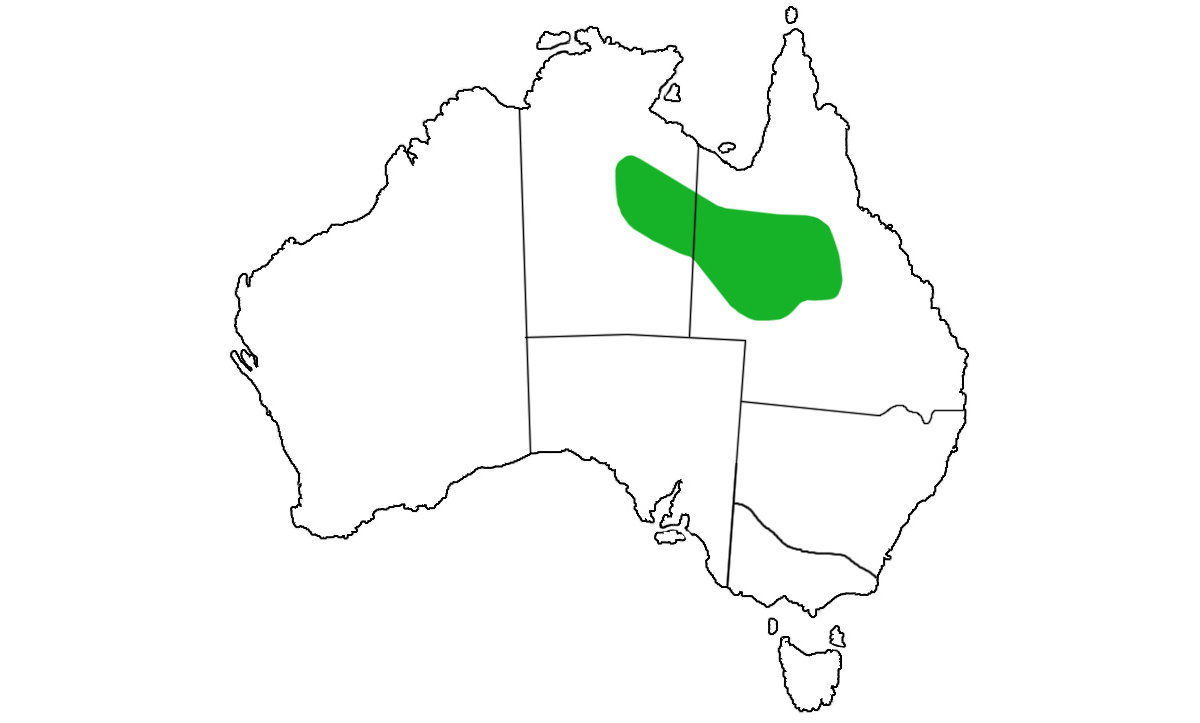

Beardies come from very hot, arid areas of Australia, living in social groups where there is lots of cover available. They can be found in natural, wild habitats and have also adapted well to living near human habitation. All animals seen in the pet trade are captive born, as Australia has a long history of prohibiting animal exportation.

Beardies are also available in a wide variety of color morphs. A few of these are single-gene mutations, such as the recently hatched albinos and an established leucistic line. High-yellow, orange and red morphs are all available, with many different names (such as Sandfires). In selecting a good color morph, buy from a reputable breeder, and try to see pictures of the adults if possible.

Like leopard geckos. "beardies" can easily be acquired through reputable pet stores, breeders, and expos. Again, it is a good idea for first-time buyers to buy locally. In addition, beardies are relatively fragile during their first month of life and react poorly to shipping. Purchase animals that are at least 1 month old. They should be active, bright-eyed and feed readily. Avoid any dragons with visibly protruding hip bones or eyes that appear to shrunken in.

Big Houses

Housing for beardies must be spacious. While a juvenile can get by in a 20-gallon, long aquarium, a single adult should have at least 4 square feet of floor space. A trio should have at least 6 square feet. As always, a secure lid is a must. Glass aquariums are not your only option, provided alternatives have enough space and plenty of ventilation. With beardies, floor space requirements are of greater importance than height requirements.

As with geckos, substrate is an important consideration. Newspaper, fine calcium or silica-based sand, mulch, bark chips or cage carpet are all acceptable substrates. Bear in mind that the amount of sand required for a large cage tends weigh quite a bit. As a result, any beardies enclosure and stand must be sturdy enough to support this added weight. Because of their voraciousness, beardies may ingest loose cage carpet fibers, so be sure to check synthetic carpets for loose strands and remove any that you discover. Periodically checking for loose fibers won't hurt, either. Upon entering your dragon's system these carpet strands can cause health problems.

As with geckos, substrate is an important consideration. Newspaper, fine calcium or silica-based sand, mulch, bark chips or cage carpet are all acceptable substrates. Bear in mind that the amount of sand required for a large cage tends weigh quite a bit. As a result, any beardies enclosure and stand must be sturdy enough to support this added weight. Because of their voraciousness, beardies may ingest loose cage carpet fibers, so be sure to check synthetic carpets for loose strands and remove any that you discover. Periodically checking for loose fibers won't hurt, either. Upon entering your dragon's system these carpet strands can cause health problems.

Beardies like the hot spot in their enclosures to be very hot. They are diurnal basking lizards, so a heat lamp is the most appropriate way to provide the extreme temperatures preferred by these hardy lizards. Temperatures around 110 degrees Fahrenheit are perfectly acceptable to beardies. However, the cage should not be this warm. Once again, create a thermal gradient by placing a basking spotlight at one end of the cage and provide good ventilation. The cool end of the cage should be in the mid 80s. If you can't provide this kind of gradient, consider a larger cage, If nighttime lows fall below the mid 70s, then an under-tank heater should be used to provide supplemental heat at night.

Furnishings for beardies should include warm and cool hide areas as well as basking spots. If you are keeping multiple dragons together, make sure the basking spots are large enough for all of them. Large rocks or bricks make good basking spots because they hold heat well. Many dragons, especially juveniles, will also use sturdy branches as basking spots. Make sure all fixtures are firmly in place, as dragons will dig a lot and can undermine furnishings, thus creating potential hazards.

Omnivorous Beardies

Beardies are omnivores, and they need as much variety in their diet as possible. Insects, especially crickets, provide a good staple diet. They must be properly gut loaded and supplemented. Dragons also relish mealworms, superworms wax worms roaches, pinky mice and anything else that moves and will fit in their mouths. Small dragons are prone to mealworm impactions, so wait until the lizards are a couple of months old before offering mealworms.

Vegetables are an important component of the beardies diet. They should receive a wide variety of leafy greens, such as mustard, collard and turnip greens, spinach, kale, and romaine and real-leaf lettuce. Again, the more variety you offer then the healthier your dragons will be. In addition to leafy greens, provide other chopped vegetables such as squash, zucchini, peas, carrots, tomatoes, string beans and peppers.

Vegetables are an important component of the beardies diet. They should receive a wide variety of leafy greens, such as mustard, collard and turnip greens, spinach, kale, and romaine and real-leaf lettuce. Again, the more variety you offer then the healthier your dragons will be. In addition to leafy greens, provide other chopped vegetables such as squash, zucchini, peas, carrots, tomatoes, string beans and peppers.

Commercial beardies foods are also available and make good addition to any dragon's diet (but still offer other foods for variety).

A good feeding schedule for young dragons is a salad mixture every morning and insects every afternoon. Young dragons have ravenous appetites and must be fed daily. Adult dragons should be fed salad three or four times a week and offered insects on a similar schedule. For larger dragons, a bowl of mealworms or superworms can also be made available at all times.

Vitamins and Supplements

Vitamin and mineral supplementation is very important. A high-calcium, high-D3 supplement should be used several times a week for juvenile dragons and breeding females, less often for older non-reproductive animals. Vitamin supplements are less important if a good variety of vegetables is offered, but should still be provided at least once a week.

Like leopard geckos, juvenile beardies don't often drink from bowls and should be sprayed with water several times per day. This is especially important as many hatchling dragons are reluctant vegetable eaters (apparently they have something in common with human children). Larger animals usually will drink from a bowl and eat their vegetables, so misting them is not usually necessary.

Breeding

Bearded dragons are easily bred in captivity. Using multiple females with one male spreads the male's attention around and prevents any one female from getting too run-down. Multiple males can be used, but subdominant males will have to be removed periodically.

Bearded dragons are easily bred in captivity. Using multiple females with one male spreads the male's attention around and prevents any one female from getting too run-down. Multiple males can be used, but subdominant males will have to be removed periodically.

Sexing dragons is not quite as easy as with leopard geckos, but with practice it is not too difficult. Mature males will have hemipenal bulges caudal to their vents. These extend further back than a leopard gecko's and are positioned closer to the sides of the tail. A split down the middle of this bulge is a good indication that the lizard is a male. In addition, males tend to be larger, have broader heads and necks, and as not as heavyset as females. Femoral pores are also more pronounced in males. Examining the hemipenal bulges is a more reliable sexing indicator than are the femoral pores, which hare a good secondary indicator.

Beardies should weigh between 7.9 and 9.6 ounces before breeding. They will breed if they're smaller than this, but are more likely to experience dystocias (difficult birth), so separate your sexes until they are ready to breed. Most dragons will reach adequate breeding size between 9 and 15 months of age.

Virgin females are generally not cycled, although older animals usually go through a cooling period. Breeders use many different cycling techniques, including length of cooling. Dragons can take temperatures in the mid 50s during their brumation, although most breeders prefer temperatures in the 60s or low 70s. If your dragons are going to be cooled below 70 degrees, make sure they have at least a week without food to purge their gut content. Length of brumation can last from one to three months.

Most breeders also manipulate day and night cycles, giving the dragons anywhere from zero to eight hours of light during brumation, and 12/12 cycles during breeding season.

When your dragons warm up, they will be ready to eat immediately. If you introduce the males at this time, you should observe courtship behavior taking place almost instantaneously. The males will bob their heads vigorously. Females will often respond with hand waving. Eventually, when females are receptive, breeding will occur.

Taking Care of Mom

Gravid females can be difficult to identify. watch for digging activity. When the female is digging, add a pile of damp sand or move her to another deep bin with damp sand. She will generally lay her eggs within a few days.

Gravid females can be difficult to identify. watch for digging activity. When the female is digging, add a pile of damp sand or move her to another deep bin with damp sand. She will generally lay her eggs within a few days.

Eggs should be removed and set up for incubation in the same manner described for leopard gecko eggs. Incubation temperatures in the low 80s are appropriate for beardies eggs. The eggs usually will hatch after about 60 days.

Bear in mind that females that are not bred may still cycle and lay infertile eggs. This can lead to a significant dystocia risk, so owners of unbred female bearded dragons may want to explore having them sprayed.

With proper care, health problems are rare. However, dragons are prone to dystocia, nutritional imbalances, impactions, and internal parasites. Be sure to work with a competent reptile veterinarian when dealing with these problems.

There are now many options available when choosing a pet lizard. As mentioned, two of the best captive-bred choices are still leopard geckos and beardies. Evaluate the needs of these lizards and decide which one is the best choice for you. If you give your pet the care it requires, you will have a happy and healthy leopard or beardies for a long time to come.

I was inside, it was outside and we were both curious. I continued to cook dinner thinking I could take a photo later.

I was inside, it was outside and we were both curious. I continued to cook dinner thinking I could take a photo later. This, apparently, was Casey. I'm very glad it wasn't a mean one! Casey became a regular at my back door during meal times. I found a bowl and put food in it every night - yes she eats out of a bowl. Some say I should have shot her, some say that I'm crazy to feed her, but it did stop her from coming in. She became a sideshow for visitors. Do I trust a crocodile? Not a chance!

This, apparently, was Casey. I'm very glad it wasn't a mean one! Casey became a regular at my back door during meal times. I found a bowl and put food in it every night - yes she eats out of a bowl. Some say I should have shot her, some say that I'm crazy to feed her, but it did stop her from coming in. She became a sideshow for visitors. Do I trust a crocodile? Not a chance!

Many years ago, we kept diamonds in our main breeding room only to watch them die one by one. Since then, and after much research and experimentation, we learnt that they cannot handle constant warm conditions. You may hear that they need UV light or that they must live outside, but this is not our experience. As long as you keep them cool most of the time and only provide basking temperatures for short periods during the day, they can thrive. We have kept them for nearly 20 years and they now flourish indoors, although we have been selectively breeding our stock from animals that tolerate the indoor life best. Currently, we have a beautiful female that is 10 years old and breeds regularly indoors (we have a clutch of eggs in the incubator as I write). Needless to say, breeding diamonds regularly indoors is not an activity for the novice though.

Many years ago, we kept diamonds in our main breeding room only to watch them die one by one. Since then, and after much research and experimentation, we learnt that they cannot handle constant warm conditions. You may hear that they need UV light or that they must live outside, but this is not our experience. As long as you keep them cool most of the time and only provide basking temperatures for short periods during the day, they can thrive. We have kept them for nearly 20 years and they now flourish indoors, although we have been selectively breeding our stock from animals that tolerate the indoor life best. Currently, we have a beautiful female that is 10 years old and breeds regularly indoors (we have a clutch of eggs in the incubator as I write). Needless to say, breeding diamonds regularly indoors is not an activity for the novice though.