The Alabama Red-bellied Turtle

/Red-bellied Turtle: The Red Profile by John E. Marshall

Alabama is home to one of the richest and most diverse herpetofauna in the United States, especially in regards to turtle species. Not counting sea turtles, at least 22 species of chelonians reside in the Heart of Dixie.

Three species - the black-nobbed "sawback" or map turtle (Graptemys nigrinoda), the flattened musk turtle (Sternotherus depressus) and the Alabama red-bellied turtle (Pseudemys alabamensis) - are endemic to the state.

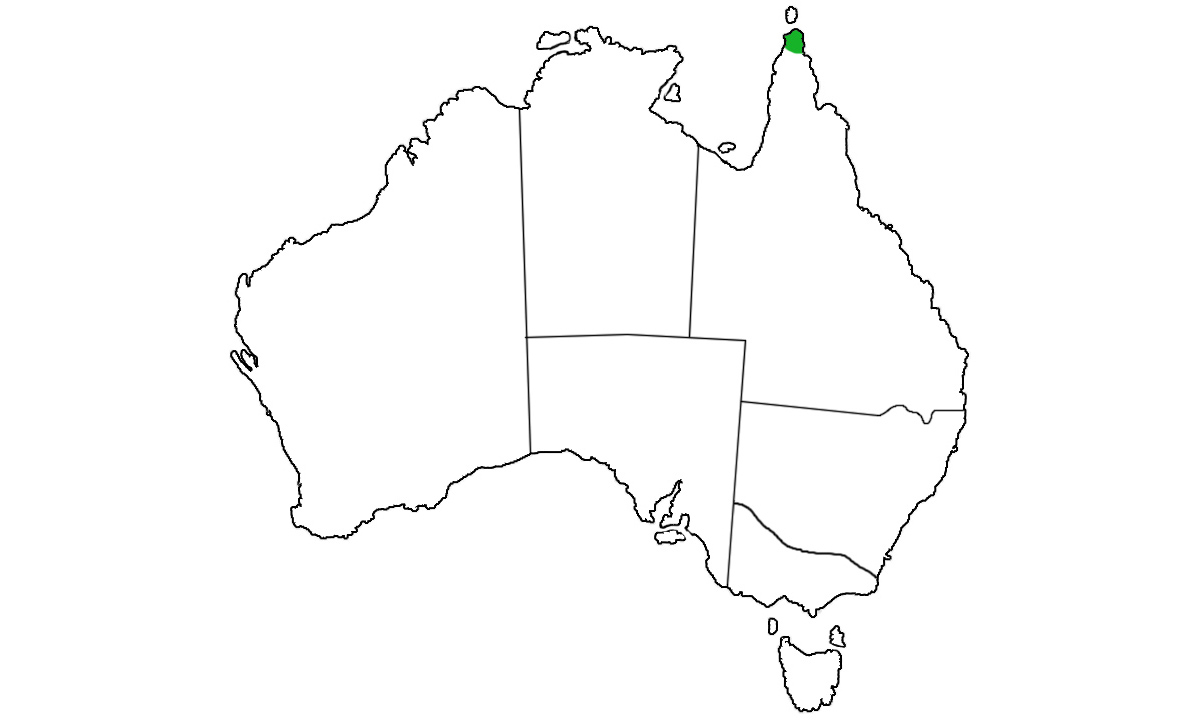

The Alabama red-bellied turtlehas the most limited distribution of the endemics. It's restricted to the rivers and swamps of coastal Alabama (near Mobile) and possibly adjoining southeastern Mississippi. It is one of the least-studied emydid turtles in North America. Until recently, little was known about its biology and ecology. Not until the 1990s, when it finally became apparent to both state and federal agencies that this species was not only endangered but rapidly heading toward extinction, did significant funding become available for in-depth research.

Description of the Red-bellied Turtle

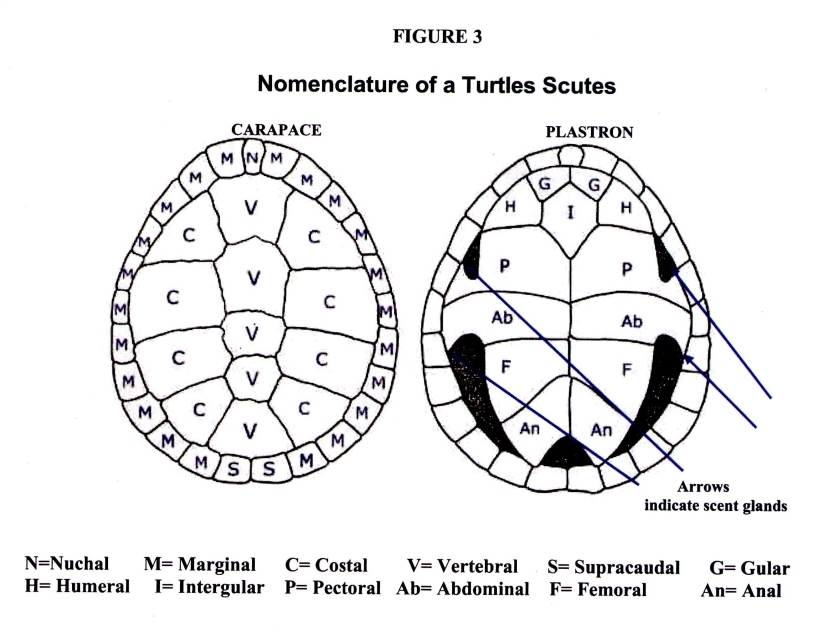

Red-bellied turtle species are large: Adult females attain carapace lengths of 12 inches and weigh 2 to 4 pounds. Males are slightly smaller with carapaces around 10 inches. The skin and carapace are a dark olive green or brown. The carapace is oval, high doomed and usually has serrations toward the rear edge.

Red-bellied turtle species are large: Adult females attain carapace lengths of 12 inches and weigh 2 to 4 pounds. Males are slightly smaller with carapaces around 10 inches. The skin and carapace are a dark olive green or brown. The carapace is oval, high doomed and usually has serrations toward the rear edge.

The species is named for its usually reddish plastron, although there is considerable variability in this color, especially between the sexes and between adults and juveniles. The plastrons of female turtles tend to be duller and more yellowish, especially in older animals. This may be the result of abrasions from sandy soils acquired during nesting season. Male and juvenile red-bellied turtle species display the more intense red or reddish-orange coloration.

Plastral markings in both sexes vary widely from plain to ornate dark bars or spots. Bars, spots and mottling on the plastron are most common in hatchling and juvenile turtles and least common in adult females.

The Alabama red-bellied turtle exhibits a variety of other sexually dimorphic features, including longer front claws and more concave plastrons in the males.

The toothlike notch or mandibular cusp, on the anterior of the upper jaw, is one of the more distinctive characteristics that distinguishes these turtles from others in the region. This feature is apparent in hatchlings and adults and tends to be more pronounced in males.

Taxonomic Quandary

The mandibular cusp and red plastron are obvious features of these turtles, but these are not sufficient to convince all scientists that Pseudemys alabamensis deserves full species status.

The mandibular cusp and red plastron are obvious features of these turtles, but these are not sufficient to convince all scientists that Pseudemys alabamensis deserves full species status.

The actual taxonomic status of P. alabamensis has been the subject of ongoing debate among herpetologists for years. Many believe it is just a a subspecies of the Florida red-belly turtle (P. nelsoni) or P. floridana (itself recently relegated to subspecies status - P. concina floridana - by Seidel, 1994). Others argue it is distinctive enough and isolated enough from Florida red-bellied turtle groups to warrant designation as a separate species. The argument is likely to continue until the respective DNA can be compared.

Many Benefactors

The Alabama red-bellied turtle has the dubious distinction of being one of the most endangered turtle in the United States. It has been listed as endangered by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Services since 1987. In recent years, the USFWS, the Alabama Division of Wildlife and Freshwater Fisheries, the Mobile District of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and the Mobile Bay National Estuary Program have funded research studies on behalf of the Alabama red-bellied turtle to better understand its basic biology, habitat requirements, distribution and estimated populations.

Dr. James Dobie, a retired professor of zoology at Auburn University, studied this species for many years and was the first to identify the primary nesting site, population distribution and precipitous decline. Dobie's research provided the basic information used by the USFWS in designating the Alabama red-belly turtle as endangered.

This research also provided the foundation upon which David Nelson, with the University of South Alabama, built his own work. From 1994 until 2000, Nelson and numerous graduate and undergraduate students conducted extensive research on red-bellied turtle movements, population and age structure, habitat and diets.

Alabama Red-bellied Turtle's Amazon

The preferred habitat of the Alabama red-bellied turtle are shallow, backwater areas off of the main river channels and smaller bays adjacent to Mobile Bay. They are especially abundant in the area known locally as the "Delta." The Delta is a huge complex of largely undisturbed wetlands stretching from the northern edge of Mobile Bay to the convergence of the Alabama and Tombigbee rivers.

This Alabama "Amazon" is comprised of over 250,000 acres of swamps, marshes, rivers and oxbow lakes. The majority of Alabama red-bellied turtles appear to be found around the Tensaw, Blakely and Apalachee rivers in the central part of the Delta and around the Causeway, an artificial land bridge that runs across the northern edge of Mobile Bay.

This Alabama "Amazon" is comprised of over 250,000 acres of swamps, marshes, rivers and oxbow lakes. The majority of Alabama red-bellied turtles appear to be found around the Tensaw, Blakely and Apalachee rivers in the central part of the Delta and around the Causeway, an artificial land bridge that runs across the northern edge of Mobile Bay.

These fresh and mildly brackish water environments provide an abundance of both submergent and emergent vegetation that turtles utilize for escape, cover and food. Nelson's studies indicate that red-bellies rarely venture into salt marshes, brackish waters (e.g., the lower portion of Mobile Bay) or small freshwater streams that are not adjacent to Mobile Bay. Apparently, these environments do not provide the dense associations of aquatic vegetation red-bellies prefer for feeding and hiding from predators.

Nelson's radio telemetry studies of 44 Alabama red-bellied turtles documented that they move more extensively within their known geographic range than previously thought. Some animals moved more than 11 miles from where they were captured and outfitted with transmitters.

Nelson's research has also documented a noticeable retraction of the Alabama red-belly turtle's earlier presumed range, at least in Alabama. Dobie found red-bellies as far north as Claude D. Kelly State Park, along the lower Alabama River. Extensive trapping by Nelson and his students in the lower Alabama River and northern Delta found virtually no Alabama red-bellied turtles and none were captured at the state park site.

The majority of turtles captured by Nelson and his team were in southern Delta and northern Mobile Bay areas, including the Mobile, Tensaw, Apalachee and Blakely rivers. This species appears to be especially abundant around the Causeway, possibly because of the dense mats of floating and submerged vegetation present there. A few animals have been captured in the southern reaches of Mobile Bay and adjacent bays, but appear to be rare in these areas.

Although this species' geographic distribution appears to have shrunk in Alabama, the discovery of a possible population in the Pascagoula River and the Back Bay of the Biloxi River in southeastern Mississippi provides some solace.

For decades it's been assumed that Pseudemys alabamensis was endemic to the lower Mobile Bay drainage basin, and that it was primarily a freshwater turtle. If the turtles found in Mississippi do indeed represent another population of P. alabamensis, it would extend the range west by about 60 miles and into two new drainage basins. These animals primarily inhabit brackish water environments, unlike their Alabama counterparts, which prefer mostly freshwater habitats.

Green Diet

Pseudemys alabamensis is a strict vegetarian. Stomach analyses have found that red-bellies feed almost exclusively on submerged aquatic vegetation, such as coontail (Ceratophyllum demersum), wild celery (Vallisineria americana) and hydrilla (Hydrilla verticillata).

Hydrilla, an exotic plant that was introduced by the aquarium trade in the 1950s, seems to be especially favored by Alabama red-bellies. Nelson's research found hydrilla to be the single most prevalent plant in their diets, even in areas where other aquatic plants were more abundant.

Under Siege

Nesting activity typically begins in April, and most nests are laid between May and August. The peak nesting period seems to be in June and July. The average incubation period is about 90 days, and hatchling usually takes place between September and November. Nelson confirmed that some eggs, probably those laid late in the nesting season, "overwinter" and hatch around March or April of the following year.

Nesting activity typically begins in April, and most nests are laid between May and August. The peak nesting period seems to be in June and July. The average incubation period is about 90 days, and hatchling usually takes place between September and November. Nelson confirmed that some eggs, probably those laid late in the nesting season, "overwinter" and hatch around March or April of the following year.

Clutch size may be as large as 20 eggs but averages about 13. Pseudemys alabamensis appears to lay more than one clutch of eggs (double clutching) during nesting season. Females captured immediately after laying a clutch have been X-rayed and found to still contain eggs.

Most Alabama red-bellied turtle habitat is affected by tidal influences. Nesting females typically select sites above the high-tide level, although nest sites occasionally flood during hurricanes and other periods of heavy rain.

The most commonly used nesting areas appear to be spoils islands constructed from the sediment dredged from the ship channels in the Delta and Mobile Bay. Alabama red-bellies also appear to prefer nest sites that are at least partially vegetated. This may be to help disguise both nests and the movements of female turtles from possible predators. Nest predation appears to be higher in areas devoid of vegetation.

Prior to Nelson's research, over 90 percent of all Alabama red-bellied turtle nest sites were believed to be on just one spoils island in the Tensaw River. Such a large concentration of the nest sites in one small area makes P. alabamensis very susceptible to a wide variety of nest predators, as well as natural disasters like storms and floods. Happily, Nelson found Alabama red-belly turtle nests on several other spoils islands as well.

Nelson and Dobie both documented the incredible level of nest predation faced by red-bellied turtles. Systematic surveys by Nelson during a two year period failed to discover even one intact nest. Feral hogs, raccoons, fire ants, opossums and fish crows all prey on P. alabamensis eggs, resulting in an estimated nest loss of over 90 percent a year.

Especially destructive are fish crows (Corvus ossifragus), which are known to watch female turtles lay and cover their eggs and then dig up the nests as soon as the turtles leave. If turtles manage to hatch, then they have to contend with the previously mentioned nest predators, plus alligators, large snapping turtles, large-mouth bass and alligator gar.

Alligator populations have increased dramatically in the Delta in recent years. In high-density alligator areas, red-bellies are scarce or absent, either because the turtles avoid these areas or because they don't last long if they wander into them. Adult alligators are probably the only serious potential predators of adult red-bellies - alligator tooth scars on many carapace indicate indicate this.

Human activities also exact a serious toll. Crab traps and boat props undoubtedly kill turtles, although no one really knows how many. But there is one area of human-induced mortality for which there is data: automobile-related deaths. Nowhere is this more evident than along the Causeway stretch of U.S. Highway 98.

During 2001, Nelson conducted bicycle surveys of the Causeway to look for signs of road-killed turtles. He documented 70 dead Alabama red-bellied turtles between April and November. Ten were adult females (five were carrying eggs), one was a juvenile and 59 were hatchlings. This is a tremendous loss of animals.

Glimmer of Hope

The State of Alabama has purchased Gravine Island and also owns Big Island and Meather State Park (on the Causeway), which protects much of P. alabamensis critical nesting habitat.

The State of Alabama has purchased Gravine Island and also owns Big Island and Meather State Park (on the Causeway), which protects much of P. alabamensis critical nesting habitat.

The next step is to increase both nesting success and survivability. Dobie proposes controlling fish crows and feral hogs to reduce nest predation. Nelson used predator-excluder covers on a trial bases and gave at least 91 turtles a fighting chance to hatch. He proposes the wider use of excluders as part of a head-start program, similar to those uses in many areas for sea turtles.

Nelson recommends installing a low fence along sections of the Causeway to prevent hatchlings and adults from wandering onto the highway. He also favors getting rid or rip-rap (large rocks used to control soil erosion along the lower Delta). Hatchlings often become trapped in spaces between the rocks.

Although no captive-breeding program is currently in place, one may have to be instituted if other measures fail to bring this species back from the brink of extinction.

Conclusion

In 1990, the Alabama Legislature bestowed upon the Alabama red-bellied turtle the auspicious title of State Reptile. This designation has done little to stop the red-belly's decline, but it has perhaps increased public awareness of its plight. Both federal and state agencies have funded research into the biology and ecology of this species, but much remains to be learned. Strides have been made, and there is now a better understanding of red-belly reproductive success (or lack thereof), movements, habitat preferences and food habits. But sound research awaits, as not enough is known about hatchling mortality, and the status and distribution of the Mississippi population needs to be addressed.

Scientists and natural resource managers are faced with the daunting task of helping Pseudemys alabamensis numbers recover while increasing public awareness. Without decisive action, questions concerning the Alabama red-bellied turtle's taxonomic status, biology and ecology will be moot, as Alabama's state reptile becomes extinct.