Freshwater Turtles: An Introduction

Turtles are one of the most appealing animals of the reptile kingdom. There are no "effort free" animals to keep as pets, and freshwater turtles are no exception. Along with the pleasure of owning a turtle comes the responsibility to provide the best possible care for it that you can. Their survival is in your hands! If basic guidelines are followed, then your turtle should thrive in captivity and may even breed for you. Freshwater turtles are renowned for their longevity and provided your pet remains healthy, may live thirty to seventy-five years in your care. This point should be taken into consideration before purchasing freshwater turtles to begin with. You may be choosing a friend for life!

Most Australian freshwater turtles are very timid and shy, but within time will loose their fear and become accustomed to you and will recognise where their food comes from. There are many stories of keepers being amused while watching freshwater turtles in their aquatic enclosures, and some go as far to say that they each freshwater turtles have their own recognizable personalities.

I believe that if more people keep our Australian freshwater turtles in captivity, then we can learn more from them and the better equipped we will be to help them. As pollution increases and swamplands are filled in for development, or rivers are dammed all in the name of progress, then we must make a concerted effort to monitor the effects that this is having on the population of our freshwater turtles. The world's most endangered turtle is the Western Swamp turtle whose numbers fell to around thirty in the 1980's. This species is currently undergoing a careful breeding program under turtle expert Gerald Kuchling and the Perth Zoo. Imagine how helpful it would have been if amateur herpetologists were already successfully breeding Western swamp turtles in captivity.

Australia has some thirty described species and sub-species of freshwater turtle and four monotypic genera. They naturally occur in all states excluding Tasmania! There are possibly many undiscovered species of turtle that have eluded the watchful eye of herpetologists due to the elusiveness and subtlety of these fascinating creatures.

Australia has some thirty described species and sub-species of freshwater turtle and four monotypic genera. They naturally occur in all states excluding Tasmania! There are possibly many undiscovered species of turtle that have eluded the watchful eye of herpetologists due to the elusiveness and subtlety of these fascinating creatures.

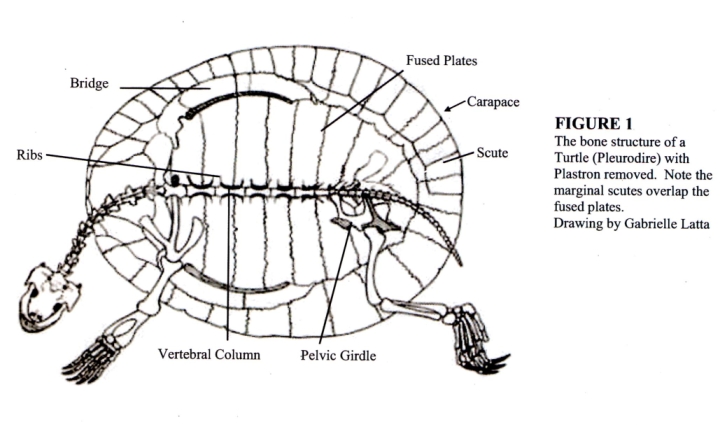

The correct zoological classifications that apply to Australian freshwater turtles are Class - Reptilia, Order - Testudines, Sub-order - Pleurodire (all except the Pig-nosed turtle which is Cryptodire). Members of the sub-order - Pleurodire, or side-necked turtles, did not evolve until the Cretaceous Period -some 135 million years ago. Reptiles in this sub-order are closely linked by the fact that their bodies are encased in a hard shell, they curl their heads back into the shell by horizontal movement and their pelvic girdle (Ref. Fig 1) is joined to the shell. Turtles are sometimes described as "living fossils" and in many respects this term is correct.

Turtle, Tortoise, or Terrapin?

The main difference is based on physiology. Tortoises are terrestrial (land dwelling) and possess thick legs and toes and require water for drinking only. There are no tortoises indigenous to Australia.

Freshwater turtles are aquatic and are not capable of swallowing food or mating unless submerged in water. They possess webbed feet or paddle-shaped, flipper-like limbs (as in the case of the Pig-nosed or Pitted-shelled turtle) and will only leave the water to lay eggs, bask in the sun or seek more favorable conditions in circumstances such as food shortage or drought. Freshwater turtles kept on dry land will dehydrate, starve, and die slowly and painfully.

"Terrapin" is merely a synonym for "Turtle" and was derived from the North American Indian word "Terrapene".

"Terrapin" is merely a synonym for "Turtle" and was derived from the North American Indian word "Terrapene".

Temperature Control (Thermo-Regulation)

Turtles are sometimes incorrectly regarded as "cold-blooded" and cannot produce their own body heat, but instead regulate their body temperature by behavioural means - (Ectothemic). Surprisingly, their body temperature can be higher than that of their environment. On warm or hot days, turtles may leave the water and bask, usually stretching their hind legs out behind them to attain maximum surface area or maximum contact with a warm surface, and will retreat into the water to cool down. Turtles have also been observed floating near the surface in warm water currents with outstretched limbs. Here they are able to capture valuable U.V. and warmth, but with the added security of being submerged. One interesting personal observation has been a turtle's reluctance to sometimes dive back into the water after it has obviously reached its preferred temperature, and occasionally submerges its head and neck in an attempt to cool down. Other turtles sometimes appear to be "crying" and are releasing fluids via the eyes as part of cooling mechanism. Basking also aids in the control of skin complaints such as fungal infections, assists in shedding scutes and helps inhibit the growth of algae on the shell. Freshwater turtles are able to gain heat much quicker than they lose it. The colour of the carapace of a turtle also plays a role in thermo-regulation. A darker carapace will heat up more quickly than a tan or other light coloured turtle, and will be able to reach a higher temperature. Heat gained through basking and ambient temperature allows a turtle's metabolism to increase.

Brumation and Aestivation

In the winter months, turtle, kept in outdoor enclosures will reduce their activity, lose interest in eating and enter a state of dormancy termed brumation. The amount of time spent brumating is governed by environmental factors and some turtles can be seen on warm winter days swimming around or sunning themselves. In colder regions of Australia such as Victoria, turtles will brumate for longer periods than more northern species. Turtles living in warmer climates such as the Northern Territory will not brumate and will remain active right through the year. Turtle's brumate either on land or in water, burying themselves in dirt and foliage or mud and sediment respectively. Those that remain beneath the water are able to absorb oxygen by means of gaseous exchange. Gaseous exchange can be performed through three different processes:

In the winter months, turtle, kept in outdoor enclosures will reduce their activity, lose interest in eating and enter a state of dormancy termed brumation. The amount of time spent brumating is governed by environmental factors and some turtles can be seen on warm winter days swimming around or sunning themselves. In colder regions of Australia such as Victoria, turtles will brumate for longer periods than more northern species. Turtles living in warmer climates such as the Northern Territory will not brumate and will remain active right through the year. Turtle's brumate either on land or in water, burying themselves in dirt and foliage or mud and sediment respectively. Those that remain beneath the water are able to absorb oxygen by means of gaseous exchange. Gaseous exchange can be performed through three different processes:

1. Pharyngeal respiration - where an extremely vascularised area at the back of the mouth will take oxygen out of the water.

2. Cloacal respiration - is achieved through thin walled sacs in the cloaca, also absorbing oxygen from the water.

3. Oxygen absorption through the skin.

It is important to note that most species cannot survive under the water for more than 2-3 hours when not in a state of dormancy.

Aestivation is when a turtle buries itself in the mud at the bottom of its waterhole or drinks as much water as it can then leaves the water and buries itself under dirt and foliage to escape drought conditions, or dangerously low levels of water. During this time, a turtle also enters a state of dormancy and slows its body processes down. Here it will remain until the water levels are restored or will perish in the event of an extended drought.

Digestion in Turtles

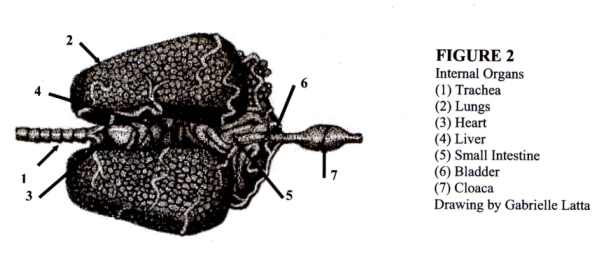

All modern turtles lack teeth. Short-necked turtles use the tough edges of their jaws to tear and dismember food. Here the clawed forelimbs also serve a useful purpose by tearing excess food away while it is firmly clamped by the mouth. Long necked turtles are essentially ambush feeders. They strike with their mouths open, drawing in large quantities of water containing their prey. Food intake of all turtles is subject to availability, and the size and age of each individual. Food intake is also temperature dependent, with most turtles ceasing to feed below 15 deg.C. Temperature also plays an important role in the time food takes to pass through the digestive system. For this reason, it is not recommended to offer food to your turtles for several weeks prior to brumation, as the food may rot in the gut and cause death. Food normally takes around 1 to 2 weeks to be completely digested. At the end of the intestinal tract is the Cloaca (Ref. Fig 2) which is where faecal and urinary waste collects and is passed. Both the male and female genital openings are also located in the cloaca. Food digested that is considered excess to the turtles growth and energy requirements is turned into fat and stored in the abdomen, rather than beneath the skin as in the case of mammals. This may be because fat stored beneath the skin could act as insulation and effect thermo-regulation.

All modern turtles lack teeth. Short-necked turtles use the tough edges of their jaws to tear and dismember food. Here the clawed forelimbs also serve a useful purpose by tearing excess food away while it is firmly clamped by the mouth. Long necked turtles are essentially ambush feeders. They strike with their mouths open, drawing in large quantities of water containing their prey. Food intake of all turtles is subject to availability, and the size and age of each individual. Food intake is also temperature dependent, with most turtles ceasing to feed below 15 deg.C. Temperature also plays an important role in the time food takes to pass through the digestive system. For this reason, it is not recommended to offer food to your turtles for several weeks prior to brumation, as the food may rot in the gut and cause death. Food normally takes around 1 to 2 weeks to be completely digested. At the end of the intestinal tract is the Cloaca (Ref. Fig 2) which is where faecal and urinary waste collects and is passed. Both the male and female genital openings are also located in the cloaca. Food digested that is considered excess to the turtles growth and energy requirements is turned into fat and stored in the abdomen, rather than beneath the skin as in the case of mammals. This may be because fat stored beneath the skin could act as insulation and effect thermo-regulation.

The Shell

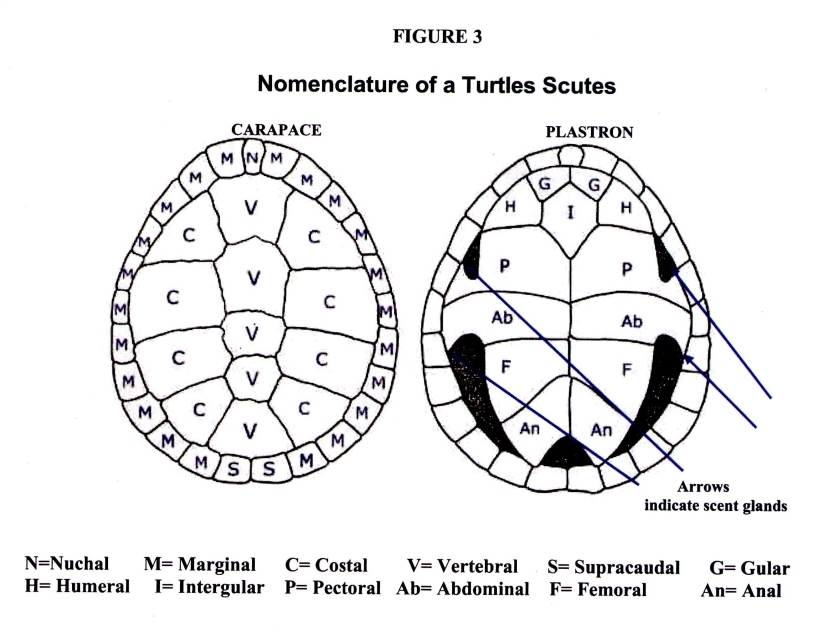

A turtle's shell is divided into two sections. The lower section is the Plastron and the upper section is the Carapace (Ref. Fig 1). The two sections are joined together by the Bridges that are located either side of the body, between the fore and hind limbs. The strength of the shell comes from the fused plates (Ref. Fig 1), which are covered by shields called scutes, lamina or scales (Ref. Figures 1+3). These shields are made from Keratin that is produced by the Malpighian cells; located just under the scutes.

A turtle's shell is divided into two sections. The lower section is the Plastron and the upper section is the Carapace (Ref. Fig 1). The two sections are joined together by the Bridges that are located either side of the body, between the fore and hind limbs. The strength of the shell comes from the fused plates (Ref. Fig 1), which are covered by shields called scutes, lamina or scales (Ref. Figures 1+3). These shields are made from Keratin that is produced by the Malpighian cells; located just under the scutes.

Circulatory System

Freshwater turtles have heart (Ref. Fig 2) with only three chambers. Many things including increased activity, temperature and increased pressure during diving affect their heart rate. An increase in ambient temperature will cause an increase in heart rate, thus increasing a turtle's metabolism. As a turtle dive, pulmonary resistance increases and the heart rate decreases. The scientific name for this is "Bradycardia". When a turtle dives, the level of oxygen in the blood decreases as the body uses it. Anaerobic metabolism takes over causing an increase in carbon dioxide. Most aquatic turtles can tolerate extremely high levels of carbon dioxide in the blood. After about 15 minutes of being submerged and the oxygen supply depleted, the brain will divert as previously mentioned, to anaerobic metabolism. Here the brain can continue to function effectively for around 2-3 hours depending on the species and size of the individual.

Respiration

Unlike the lungs of mammals, a turtle's lungs (Ref. Fig 2) are not maintained at positive pressure. The ribs of a turtle are joined to the shell (Ref. Fig 1). Breathing is performed with help of muscles that are located near the limbs at four corners of the shell. These muscles create a negative pressure in the lungs and respiration takes place. Inspiration occurs due to the difference in pressure. Expiration, however, does take some degree of effort. When a turtle enters the water this situation is completely reversed due to the increase in water pressure. Inspiration now requires muscular activity, and expiration is aided by the water pressure and takes little or no effort. The amount of air in the lungs and the transferral of fluids within the bladder and cloaca control a turtle's buoyancy. Proof that the lungs help control a turtle's buoyancy is clear when watching a turtle with a respiratory infection. turtles suffering from respiratory infection cannot dive and have been observed floating at unusual angles (pers. obs).

Sight, Smell and Hearing

A turtle's senses of vision, smell and hearing are highly developed which is necessary for locating food, avoiding predators and important in finding suitable mates during breeding season. It has been suggested that they possess colour vision and this may be why some turtles show colour preferences when feeding. All freshwater turtles have a thin, transparent third-eyelid, called a nictitating membrane that covers their eye while they are submerged to allow them to see proficiently under water. Their sense of smell is achieved through the nose and also through a specialise structure called Jacobsen's organ. Jacobsen's organ is located in the roof of the mouth. Its function is to detect and identify tiny chemical, scent particles that are floating around in the air and water. The scent particles are moved around the mouth and throat by "gular pumping" (throat movements similar to that of frogs.) We have observed many species of freshwater turtles' gular pumping while submerged. Turtles do not have external ear opening instead they have a tympanum (eardrum) that is covered with skin. The inner ear is surrounded by a bony box-like structure known as the otic capsule. Turtle's hearing is at its best detecting low-frequency vibrations under water and to lesser extent, on land. Their ability to hear medium to high frequency sounds is difficult to determine. All Australian turtles have four scent glands, one on either side of each bridge, near the limb pockets (Refer arrows on Fig.3). The odour produced is used as a defence mechanism against predators, and possibly with other males when they feel threatened while competing for the same female during breeding season.

A turtle's senses of vision, smell and hearing are highly developed which is necessary for locating food, avoiding predators and important in finding suitable mates during breeding season. It has been suggested that they possess colour vision and this may be why some turtles show colour preferences when feeding. All freshwater turtles have a thin, transparent third-eyelid, called a nictitating membrane that covers their eye while they are submerged to allow them to see proficiently under water. Their sense of smell is achieved through the nose and also through a specialise structure called Jacobsen's organ. Jacobsen's organ is located in the roof of the mouth. Its function is to detect and identify tiny chemical, scent particles that are floating around in the air and water. The scent particles are moved around the mouth and throat by "gular pumping" (throat movements similar to that of frogs.) We have observed many species of freshwater turtles' gular pumping while submerged. Turtles do not have external ear opening instead they have a tympanum (eardrum) that is covered with skin. The inner ear is surrounded by a bony box-like structure known as the otic capsule. Turtle's hearing is at its best detecting low-frequency vibrations under water and to lesser extent, on land. Their ability to hear medium to high frequency sounds is difficult to determine. All Australian turtles have four scent glands, one on either side of each bridge, near the limb pockets (Refer arrows on Fig.3). The odour produced is used as a defence mechanism against predators, and possibly with other males when they feel threatened while competing for the same female during breeding season.

Keeping Turtles Indoors

It is recommended to keep small turtles up to seven centimetres shell length indoors where they can be easily monitored. A 3-foot or 4-foot long aquarium is recommended. the aquarium should have 3-4 centimetres of river gravel and be a half to two-thirds full of water. The aquarium should also contain a log that protrudes above the surface of the water, or an artificial platform, so the turtles may leave the water to bask and dry out. Choose a log that has been collected from a creek or steam as dry timber will float and discolour the water. There are some commercially available floating islands like the Zoo-Med "Turtle dock"or the Herp Craft "Floating Land" products that are inexpensive and highly recommended. The "basking areas" should be situated directly below the sides of the aquarium where the glass lids can be removed.