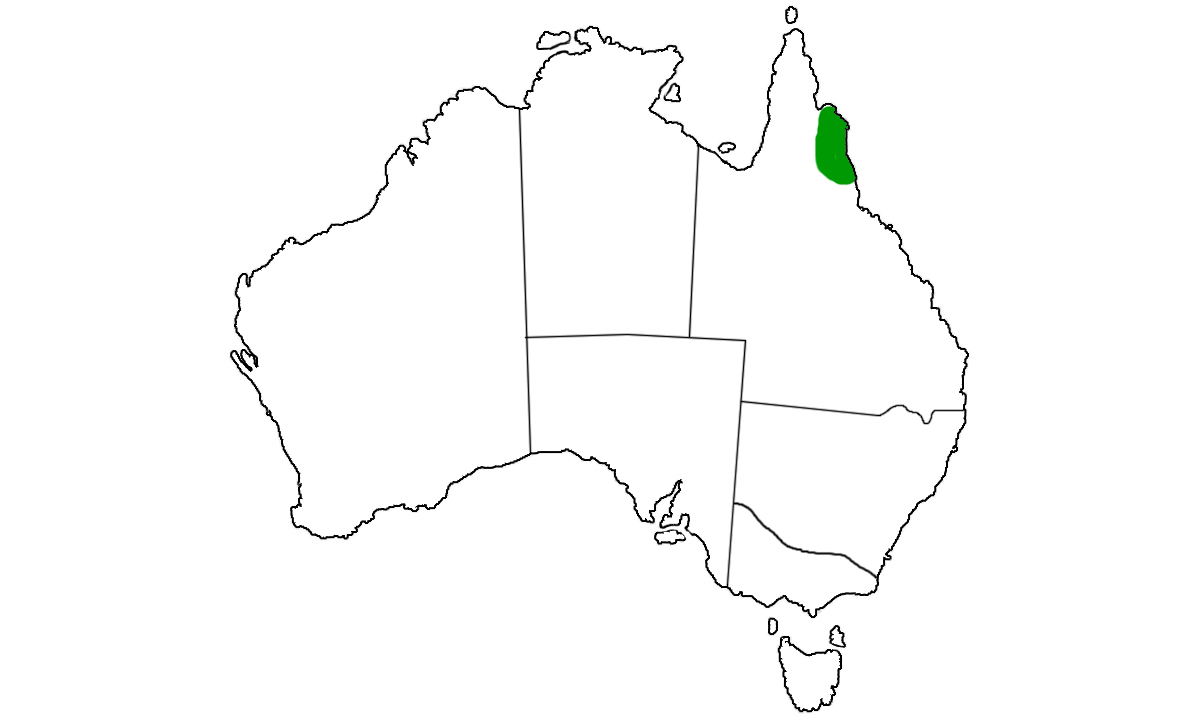

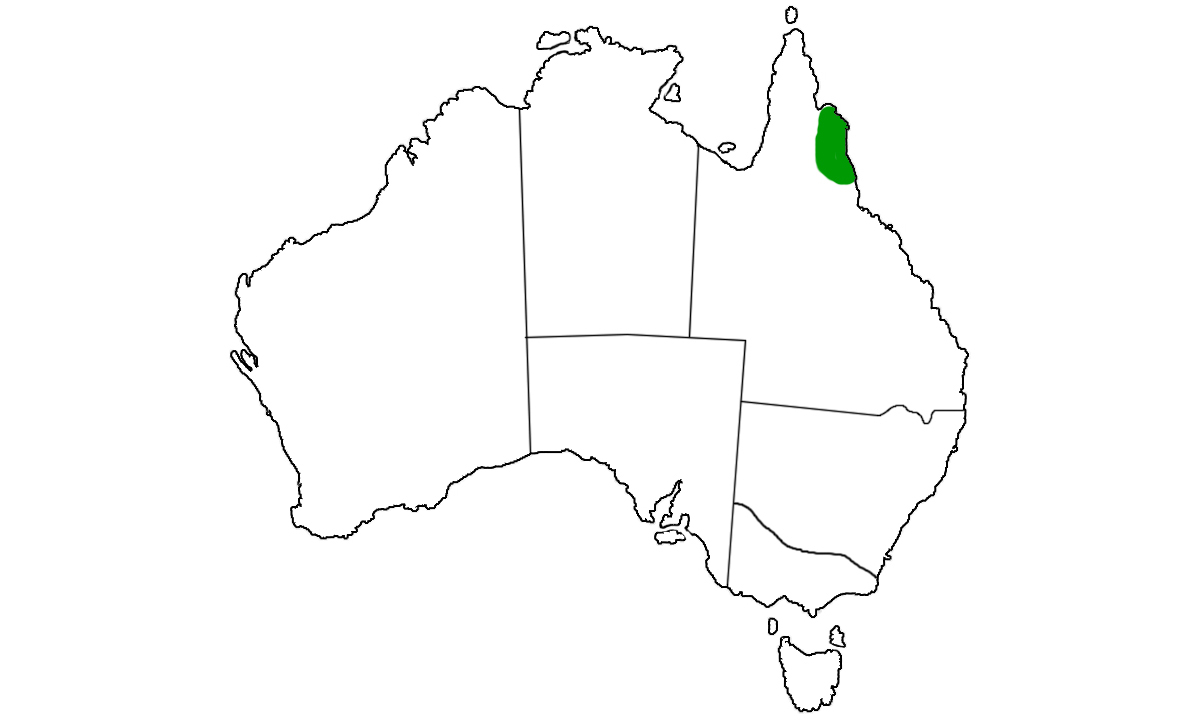

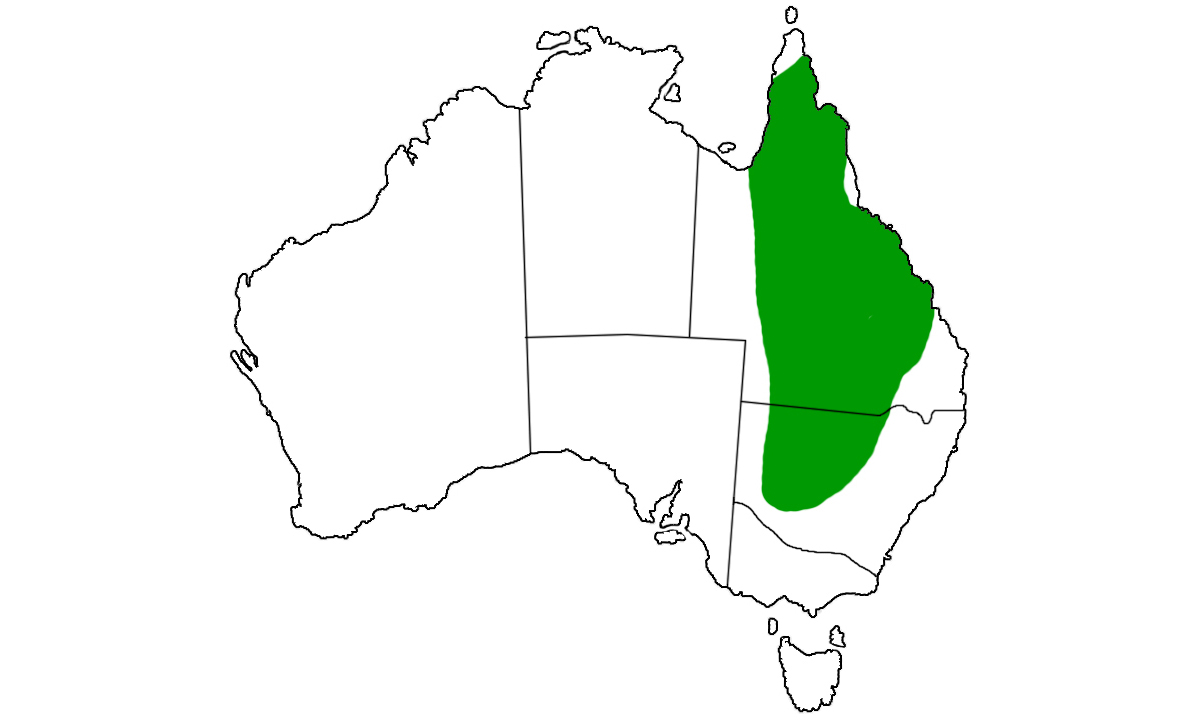

In June 1995 I decided to initiate a breeding program for Frill-necked lizards (Chlamydosaurus kingii)

by David Klier (Originally published in Monitor Vol. 9 No. 2 April 1998 Housing).

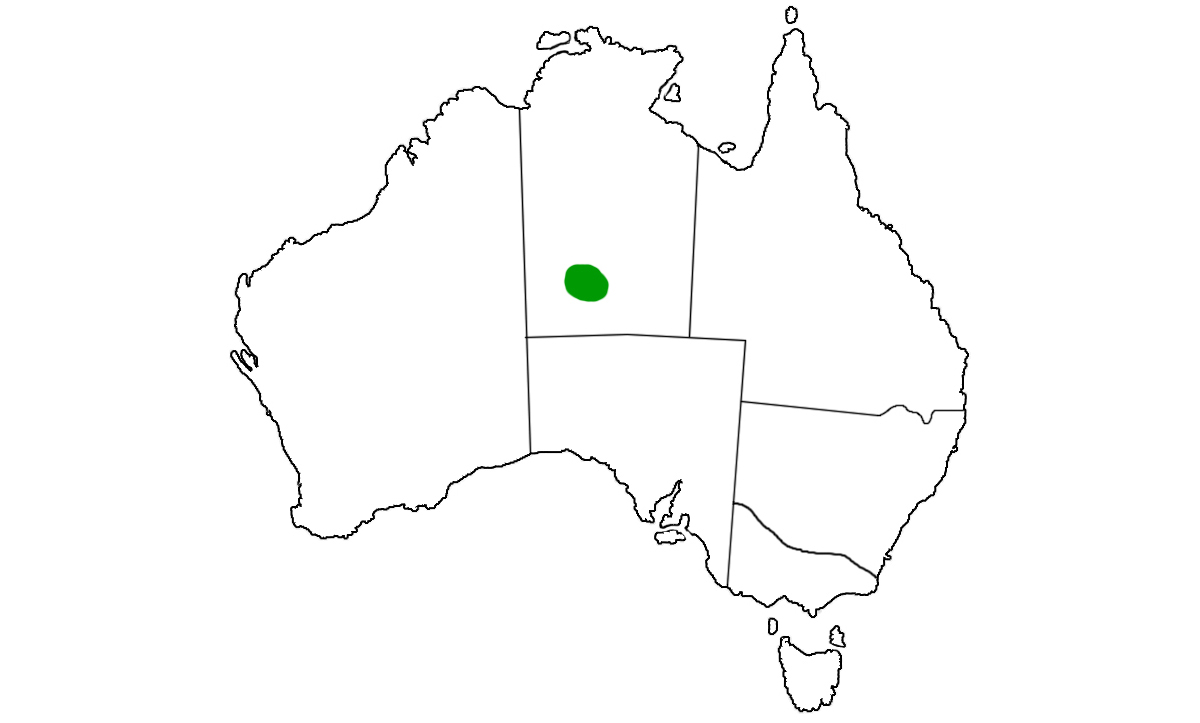

I had 8 Frill-necked lizards from the Northern Territory, 6 of which were old enough to breed; of these 2 were females, the remaining 4 were males. The adults were between 14 months and 5 years of age.

The breeding colony of the frill-necked lizards was housed in a cage 7 foot (210cm) long and 5 foot (150cm) high and 3 foot (90cm) in depth. Heating was supplied by 6 globes and was thermostatically controlled. In addition to this, one 4 foot double florescent was installed to provide UV and full spectrum lighting; all of this was controlled by a timer.

Upright vertical branches were supplied for the frill-necked lizards to perch on. The branches were placed so the Frill-Necked Lizards could bask close to the heat source. The substrate consisted of a fine red soil about 1 inch deep.

Since the original housing arrangements I’ve extended the herp house and built a new indoor/outdoor enclosure for the Frill-Necked Lizards. The dimensions now being 12 foot (3600cm) long, 7 foot (210cm) deep and 7 foot (210cm) high. The enclosure is fully insulated with a large window on the northern side for sun. It has a skyroof with a sliding door to close, in cold conditions. All windows are fully insulated. The enclosure is heated with 6 x 250 watt heating lamps, five are mounted on the ceiling and one mounted part of the way down one wall, as well as natural sunlight. Heating is controlled by a thermostat.

A misting system was installed overhead to increase humidity during the wet season, which is controlled by a timer.

The enclosure is landscaped with numerous branches and indoor plants, example: indoor fig trees, grass trees, palms etc. As well as the Frill-Necked Lizards being housed in the enclosure there are four adult Land Mullets (Egernia major) and two adult Gidgee Skinks (Egernia stokesii) all of which seem to get along with each other.

Breeding Initiation of the Frill-Necked Lizards

On the 1st of June, 1995 I decided to cool the Frill-Necked Lizards and decrease their daylight hours. I cooled them down to a daylight temperature of approximately 29°C and the nightly temperature to approximately 18°C. The timer was set for a nine hour day and a fifteen hour night. I kept this procedure going for the months of June and July. The humidity in the cage was approximately 34%. During this time the cage was kept dry with no water spraying. The Frill-Necked Lizards were given water directly from a small bottle every 2 to 3 days.

On the 1st of August, 1995 daylight hours were increased to 12 hours. The temperature was increased to approximately 33°C in daylight and 22°C at night. I began spraying the cage twice weekly. This procedure was done by using a 2 litre pressure pump spray bottle. The entire cage was sprayed, including the walls, branches, ground and lizards, with about 1 litre of water. This increased the humidity to approximately 50%. On the 12th of September daily spraying commenced, thus increasing the humidity to between 70 and 80%.

Frill-Necked Lizards: Mating

I first noticed mating behavior towards the end of August from one of the smaller males, this consisted of the head bobbing, with frill extended and circular arm waving motion. However, this lasted only a couple of days due to another male being more dominant, this male was the same age but a lot larger. Although I never witnessed any fight between these two males I believe there would have been a fight or conflict of sorts for dominance. From that point in time the larger male had complete control over the other 3 males, who would shy away whenever the large male would begin his mating.

Since daily spraying began mating behavior had increased to a high level with the large male bobbing his head and waving his arm regularly throughout the day.

The females would respond by pointing their nose straight up in the air, waving their arm in a circular motion and lifting their bodies up on all four legs.

The male was observed chasing the females on a number of occasions. On the 22nd of September 1995, I witnessed copulation between the dominant male and the youngest female (17 months old, length in total was 19 inches (47.5cm)).

I noticed that for 2 days after copulation the female stayed high on the branch without descending, when she did descend she walked around on all four legs swaying her body from side to side with her head lowered and moving in a circular motion. Her frill was half erect. This behavior continued all breeding season. I feel this behavior was a signal to tell the male she was gravid, because I noticed the male did not bother trying to mate with her again until after egg laying.

On the 13th of October, 1995 copulation was notices with the older female (4½ years old, length in total 23 inches (57cm)), this was noticed twice within half an hour. Her behavior was identical to the younger female.

After I witnessed the actual mating with the younger female I decided it was time to set up and area in the cage for egg laying.

Preparing the Frill-Necked Lizards for Egg Laying

I used as area of approximately 3 foot (89cm) square with a depth of 10 inches (25cm). I partitioned this area off with two large logs in order to retain the egg laying medium.

The medium consisted of two thirds garden loam and one third peat moss. This was well mixed together. After the medium was in place I watered the area until it was fairly moist. With the daily water spraying the medium was sprayed as well to keep the area moist. After I added the medium I found it to be of a great benefit in keeping the humidity at the level I wanted.

Frill-Necked Lizards: Laying of Eggs

On the 14th of October, 1995 the younger female deposited a clutch of 9 eggs in a hole she had dug in the corner of the cage in the prepared medium. All eggs appeared to be fertile so I removed them for incubation.

A second copulation was noted on the 24th of October, 1995 and four weeks later on the 22nd of November, 1995 the female laid a second clutch of 12 eggs, laying them in exactly the same place as the first clutch. These eggs appeared fertile and were removed for incubation.

All eggs were approximately 30mm (just over an inch) in length when deposited. No weights were measured.

A large clear sealed container was used for the incubation medium, which consisted of 815gm of medium sized vermiculite mixed with water to a one to one ratio. In the lower half of the container a hole was drilled so the probe from the digital thermometer could be placed inside the container just under the surface of the vermiculite to read the temperature. I adjusted the incubating temperature to between 29 and 30°C. Humidity was 95% plus.

All eggs incubating were monitored at least once a week to check progress and to remove and that may have died. Approximately 52 days after the first clutch was laid one egg appeared to have died. The egg was removed and opened for inspection. Inside was a partly formed baby that had died. The only reason I could come up with was that this was the egg I had accidentaly dropped when initially collecting them and it was not placed in the container correctly due to not knowing which way it had been laid. All other eggs were developing well and all looked very good. Growth in the first clutch was astounding. By 2 months of incubation the eggs had more than doubled in size, and still had approximately 20 days to go.

In the meantime the second clutch which was in the same container was developing well with slight growth noticed as approximately 30 days incubation, but looked small compared to the first clutch of eggs.

Egg Hatching of the Frill-Necked Lizards

First clutch. Between the 2nd and 3rd of January, 1996 exactly 80 days after being laid, the first two baby Frill-Necked Lizards slit their eggs and hatched out overnight. It was a great felling to see these beautiful little Frill-Necked lizards out of their eggs alive and well, both were removed from the incubator. I measured and weighed them then placed them in their cage. During the first night more eggs were slit and more babies emerged, some babies had their heads protruding. The following morning, 4th January, 1996 two more babies had hatched out with the remaining two babies hatching later that day, so all eight babies hatched over a two day period and all were fit and healthy.

Second clutch. The second clutch of 12 Frilly eggs started hatching on the 10th of February, 1996. After 80 days incubation, all had emerged by the end of the day on 11th of February, 1996.

Housing and Feeding of Baby Frill-Necked Lizards

All babies were housed in 4 foot aquariums and provided with a 2 foot fluoro (full spectrum) and a basking lamp to provide a hot spot. Air temperature in the aquariums was approximately 32°C.

All babies began feeding within a couple of days of birth. The food consisted of small crickets, cockroaches and small white meal worms. I decided to have a daily feeding routing for the babies with every alternative day the insects being dusted with Repcal and Herp-Vite multi vitamins and minerals, then one day off feeding for the week. The aquariums were lightly sprayed daily and babies were given water from a spray bottle to drink, all accepted this very well.

With this feeding pattern in place the growth rates of the babies was very good. Measurements were taken on the 23rd of April, 1996 of the length and weight of the remaining babies from both clutches after the sale of the others.

Frill-Necked Lizards: Breeding

Female No. 1 has yet to produce a god clutch of eggs, the reason for this is unknown but on both occasions when gravid she dropped the eggs from the branch she was perched on. The first clutch of eggs were retained for months after they were actually due for deposition, being dropped in April 1996. The second clutch were dropped at the right time but were no good after being dropped from a height. Eggs from both clutches were examined, with most proving to be infertile but a number of them having embryos.

All eggs from female No. 2 were fertile and developed well during incubation, apart from the second clutch in 1996 in which the eggs developed at a slower rate and did not increase in weight to the same size as the first clutch.

As can be seen by the data on the 2nd clutch (Female No. 2) the babies were born smaller and lighter in weight, this is due to a minor mistake on my part. Instead of setting up a new container for incubating I used the same container which was used for the 1st clutch, obviously the moisture content had reduced enough for the eggs to develop at a slower rate and not increase to the size of the 1st clutch, as indicated by the weights of the eggs taken just prior to hatching. Unfortunately a couple of the babies were weak at birth and one died after 53 days. As you can see by growth rates after 35 days the babies are only now reaching the size of the babies from the 1st clutch at birth. Apart from the other ill baby all appear to be progressing well and appear to be healthy and without problems.

Sexing Baby Frill-Necked Lizards

This proved to be very difficult because the babies were small. Brian Barnett and I attempted to extrude the hemipenes but this was short lived because the babies were too small and delicate. Later, with the use of a magnifying glass I decided to try to count the pre-anal pores which in itself worked well, except for the inconsistency in the number of pores counted on each animal which ranged from 6-8 on different animals. It was decided to leave sexing until the animals old enough to physically see the changes in the animals.

Acknowledgement

Brian Barnett provided guidance and assistance during this project and helped ensure my successful breeding of Frill-Necked Lizards.

Table 1. Breeding Data 1995-96

| Female | Date Deposited | No. of Eggs | Length | No. Hatched |

| No. 1 | 25 April 1996 | 8 | 32mm | 0 |

| No. 2 | 14 October 1995 | 9 | 30mm | 8 |

| No. 2 | 22 November 1995 | 12 | 30mm | 12 |

| No. 1 | 23 December 1996 | 10 | 32mm | 0 |

| No. 2 | 13 September 1996 | 11 | 30mm | 11 |

| No. 2 | 9 December 1996 | 10 | 30mm | 10 |

Table 2. Hatching Data 1995-96

| Date Hatched | Inc. Period | No. Hatched | Ave. Length | Ave. Weight |

| 3 January 1996 | 80 days | 8 | 140mm | 3.8g |

| 10 February 1996 | 80 days | 12 | 138mm | 3.6g |

| 28 November 1996 | 79 days | 11 | 138mm | 4.0g |

| 25 February 1997 | 78 days | 10 | 102mm | 3.8g |

Table 3. Growth Rate of Babies

| Date Hatched | Days Old | Ave. Length | Ave. Weight |

| 3 January 1996 | 30 | 178mm | 4.8g |

| 3 January 1996 | 110 | 242mm | 10.5g |

| 10 February 1996 | 30 | 152mm | 4.7g |

| 10 February 1996 | 70 | 216mm | 9.0g |

| 28 November 1996 | 38 | 165mm | 5.0g |

| 28 November 1996 | 150 | 178mm | 10.3g |

| 25 February 1997 | 35 | 133mm | 4.3g |

| 25 February 1997 | 70 | 127mm | 4.7g |