Kids and reptiles! Can they mix and should they mix?

by Kerrie Alexander

In my opinion yes and sometimes no. In this article I will express some ideas and tips on how to keep the harmony with our kids and reptiles, and also perhaps when we should draw the line.

In my experience with demonstrating reptiles to children I have found 80% are keen to touch and are waiting with lots of questions. This is, of course a fantastic learning experience, but like most things children need some guidance. They need to be shown how to treat and hold the animals in order to understand how these little creatures work.

Usually the children are set some basic rules. These rules are easy for them to understand and are always said in a positive way.

Usually the children are set some basic rules. These rules are easy for them to understand and are always said in a positive way.

Kids and Reptiles: Examples of rules for children when handling reptiles are as follows:

* Only touch the back, tail or tummy, as they do not like to be touched on the face. (If asked why? we simply ask if they liked being touched all over the face by a stranger, no is usually the answer.) Facing the animal with its tail towards people is the best way to solve this.

* Make sure you support the animals’ legs when holding and do not squeeze, just let them sit or slide through your hands.

* Never poke the animal or do anything that you yourself wouldn’t like.

* Make sure you wash your hands after touching the reptiles.

There is always the other 20% of children who don’t feel comfortable holding or touching the animals - they prefer to just look and this is fine.These children can still learn a lot and sometimes they just need a bit more time to watch you hold the animal and understand them before they feel comfortable. I actually prefer this as I know that they will respect the animal and have some understanding of it. This is better than the children diving in and maybe hurting the animal because they have not listened.

There are times when lines are drawn and strict rules need to be in place. Examples of this include instances when venomous snakes or larger, more dangerous animals such as goannas are being shown. Of course when demonstrating venomous snakes and some larger goannas, the animals should only be touched by or come close to the demonstrator.

There are times when lines are drawn and strict rules need to be in place. Examples of this include instances when venomous snakes or larger, more dangerous animals such as goannas are being shown. Of course when demonstrating venomous snakes and some larger goannas, the animals should only be touched by or come close to the demonstrator.

When keeping venomous snakes privately they should always be housed in a locked enclosure, off the ground and out of the child’s reach. One effective system used by many keepers to clearly identify potentially dangerous animals is the colour system. A sticker or coloured piece of paper is placed on every enclosure that contains an animal. Dangerous animals are identified by a red sticker, while harmless animals have blue or green. Red, even to the smallest child is associated with hot, stop, dangerous etc and therefore clearly identifies the animals children should never try to touch. Blue or green are associated with calming, go, cold etc. and children can therefore recognize harmless animals.

My daughter, Chloe, 5yrs, has shown a fantastic interest and respect for reptiles. We have been lucky that she keeps a safe distance and obeys our rules when dealing with venomous snakes and their removal. Such a thing cannot be expected by every child and each needs to be assessed individually if they are to come close to these animals. I do not promote or encourage venomous snakes and children to mix.

My daughter, Chloe, 5yrs, has shown a fantastic interest and respect for reptiles. We have been lucky that she keeps a safe distance and obeys our rules when dealing with venomous snakes and their removal. Such a thing cannot be expected by every child and each needs to be assessed individually if they are to come close to these animals. I do not promote or encourage venomous snakes and children to mix.

Reptiles can be a fun and exciting experience for children and encourage responsibility along with a greater understanding of our native animals and how they live.

Kids and Reptiles: The best first reptiles or invertebrates for children are:

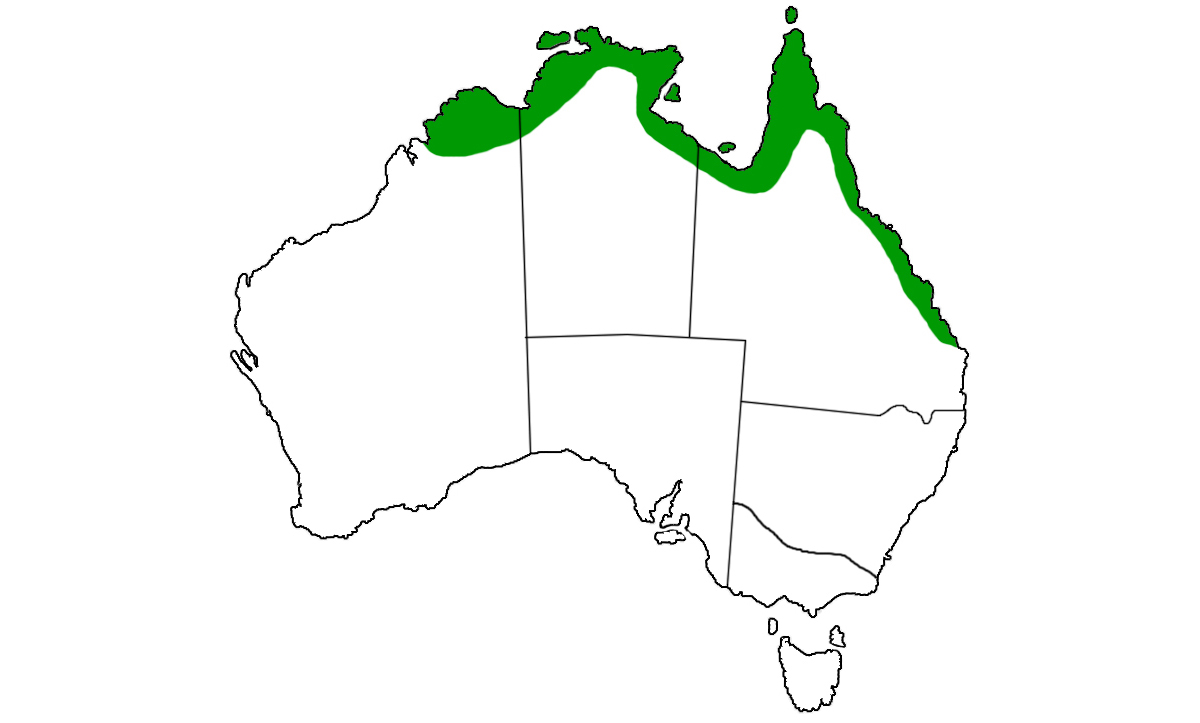

- Blue tongue lizards

- Shingle back Skinks

- Bearded dragons

- Long neck Turtles

- Children’s Python or equivalent

- Green Tree Frogs

- Stick insects

These animals can be obtained through your local breeder or pet store. No animal should be taken from the wild.